Lab Writeup: PortSwigger – 0.CL Request Smuggling

First-person, A complete, beginner-friendly walkthrough of PortSwigger’s new 0.CL Request Smuggling lab. Includes detection techniques, exploitation methods, ERG choices, and defensive strategies.

⚠️ Disclaimer

This write-up is for educational purposes only and intended for legal, controlled environments such as PortSwigger’s Web Security Academy. Do not apply these techniques to systems without proper authorization.

1 - Introduction

When I opened the PortSwigger 0.CL Request Smuggling lab, the lab description was clear:

Goal: Carlos visits the homepage every five seconds. Exploit the vulnerability to execute

alert()in his browser.

So my job was simple to state and tricky to execute: make Carlos’s browser run a JavaScript alert() by abusing a 0.CL request smuggling desync.

In this blog I write what I actually did - step-by-step, in plain language. I explain why each step matters, why I chose certain endpoints, and how defenders can prevent it.

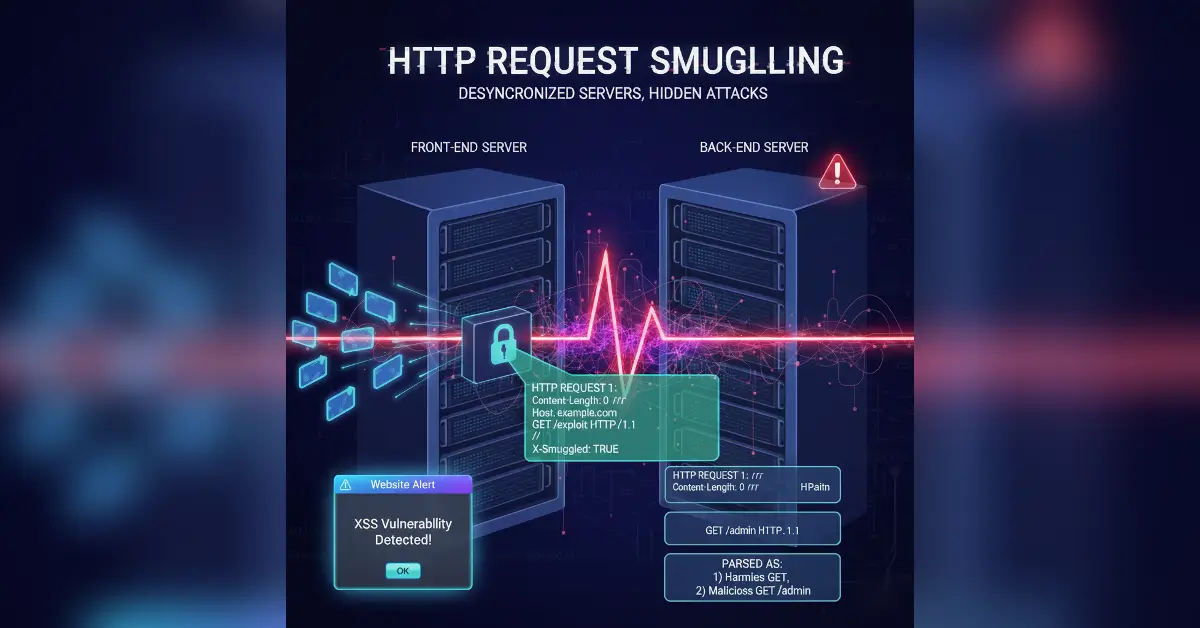

2 - Quick background

Request smuggling happens when two servers disagree about where one HTTP request ends and the next begins. In this lab, the mismatch is 0.CL: the front-end ignores Content-Length: 0, but the back-end respects it and reads a body that the front-end didn’t expect. That mismatch lets us sneak a new request past the front-end. It doesn’t see it, but the back-end does - and runs it like a normal request.

Beginner breakout: Imagine two people reading a letter. The first one thinks the letter ends after the first page because it says 'End of letter' (Content-Length: 0). So they pass the rest along without reading it. But the second person sees that there’s more and reads the next page as a whole new letter (Content-Length: 4). If you sneak in secret instructions on that second page, the second reader treats them as a new, valid message. That’s 0.CL request smuggling.

Reference reading: PortSwigger research on HTTP desync attacks and RFC 7230 for request framing rules.

3 - Recon: where I started

I began with basic recon in Burp Suite:

- Set my browser to proxy through Burp and opened the lab.

- Visited the homepage and a few static pages, recording all requests in HTTP history.

- Looked for unusual headers and values - especially

Content-LengthandTransfer-Encoding.

What I found:

- Some responses hinted that static asset endpoints behaved differently.

- I spotted places where the app returned content after tiny requests (good sign for ERG selection later).

4 - Confirming the 0.CL behavior

Before building anything, I wanted to verify that the back-end would accept a smuggled request when Content-Length: 0 was used.

Manual check with Repeater (grouped test):

-

In Repeater, I composed:

(Note: the

GET /404is placed after an empty POST body - intentionally.) -

I sent the whole combined unit and watched the response.

-

If the second request (GET /404) is processed unexpectedly (for example the server returns a 404 or an unexpected result), that indicates a 0.CL desync.

This quick Repeater test confirmed the lab’s 0.CL behavior for me.

Why this matters: I didn’t blindly jump to an exploit. First I checked that the back-end would indeed treat the following text as a new request.

5 - Finding the XSS injection point

The lab goal is to execute alert() in Carlos’ browser. To solve the lab, I needed to find a place where I could inject JavaScript, and it would show up when Carlos visits the homepage. I searched the app for reflected data that would be rendered in the victim’s page:

- I tested common places: URL params, form fields, and headers.

- I observed that the User-Agent header was reflected in responses (it’s common in some apps to echo a header into HTML or into debug pages).

- I confirmed the reflection in Repeater by setting

User-Agent: a"/><script>alert(1)</script>and checking if the returned HTML included the raw payload.

Important: I only used harmless alert(1) payloads in the lab environment to avoid causing harm.

Result: The User-Agent header was reflected back into the HTML, so it could be used to inject our XSS payload.

6 - Choosing the ERG (why endpoint choice matters)

I needed a reliable Early Response Gadget (ERG) — an endpoint that responds quickly and predictably. In testing, static resource paths (for example /resources/css/anything) tended to provide stable, fast responses which made timing and ordering in the smuggling chain easier.

Why ERG matters:

- A fast ERG reduces timing uncertainty when you're queuing multiple requests over one connection.

- If an ERG is slow or varies, the smuggled request may not be processed the way you expect.

So I selected a static asset path as my carrier point (ERG), because it made the exploit more stable in repeated runs.

7 - Building the smuggling chain (Turbo Intruder)

Manual single-shot requests are flaky for 0.CL. I used Turbo Intruder to control raw TCP ordering and timing. Below is the structure I used — I’ll explain each piece in plain language.

Stage 1 (carrier request) — the front-end sees this first

%sis a placeholder Turbo Intruder will fill so I can precisely control lengths.

Smuggled request (the secret we want the back-end to process)

- I put the XSS payload into the

User-Agentheader because I confirmed it’s reflected in the victim page. - The small body

x=1is just to make the request well-formed.

Stage 2 (connection shaper) — keeps the flow predictable

- Some servers reject GETs with bodies, so I use

OPTIONSor another tolerant method to avoid rejections and keep connection state stable.

Victim request — what Carlos will request

- This is the simple homepage request that Carlos requests periodically. If the smuggling worked, the XSS will be reflected when Carlos loads this page and his browser will execute

alert(1).

How Turbo Intruder runs them I queued Stage 1, then the Stage 2 + smuggled request, then the victim request. Turbo Intruder sends these in the same TCP stream so the back-end parses the smuggled GET as a distinct request while the front-end thinks it's body data.

8 - Running the attack and watching Carlos

I launched the Turbo Intruder script and watched the Burp/Turbo console:

- The script loops these sequences until it sees a success indicator (I set it to look for the lab “Congratulations” text or a page that contains the injected payload).

- Because Carlos refreshes every five seconds, I watched for a short while for the alert to appear.

Success signs I looked for:

- A response containing the injected string showing up in the victim page HTML.

- For PortSwigger labs, the “Congratulations” message or explicit lab success indicator.

When the injection reflected in the victim response, Carlos visited the homepage and the XSS ran — the lab marked it as solved automatically.

9 - Troubleshooting (what failed and why)

If it didn’t work right away, these are the common issues I debugged:

- Missing CRLFs or spacing: A single missing

\r\ncan break parser boundaries. I double-checked that each request ends with\r\n\r\n. - Wrong ERG choice: Some endpoints are slower or proxied differently — try a few static asset paths.

- Server rejects GET with body: Replace

GETbody with anOPTIONSor use a minimalContent-Lengthon the smuggled GET with a tiny body. - Connection closing too early: Reduce concurrency, lower the rate, or add tiny delays (Turbo Intruder supports this).

- Turbo Intruder

%splacement: Forgetting%sin Stage 1 stops Turbo from calculating lengths — always confirm it’s present.

I iterated on these fixes until the XSS reflexed reliably.

10 - Defensive perspective (how to stop this)

This section is the most critical for defenders.

Code and config level fixes

- Ensure consistent HTTP parsing at the proxy and application layers. Terminate and re-encode requests at a single boundary when possible.

- Reject ambiguous requests — for example, requests that contain both

Content-Lengthand Transfer-Encoding or oddContent-Length: 0uses. - Upgrade and patch proxies (Nginx, HAProxy, Apache) and application servers to versions that address known desync bugs.

Monitoring & detection

- Log and alert when the body contains unexpected HTTP verbs (

GET,POST) or whenContent-Lengthmismatch occurs. - Instrument front-end proxies to log raw request bytes for suspicious sequences.

- Use WAF rules to detect early response gadgets or repeated unusual patterns.

Developer tip: Add automated tests that send malformed requests. If front-end and back-end parse differently, your CI/CD test should fail.

11 - Final thoughts (what I learned)

Solving this lab taught me that:

- Small differences (a single

0) can break server synchronization. - The practical exploit requires careful staging (ERG choice, request shaping, timing).

- Always think defensive — understanding the exploit is how you design the fix.

If you’re practicing this lab, take your time with the Repeater test, pick a stable ERG, and iterate on your Turbo Intruder script. When you see that alert() in Carlos’ browser, you’ll have a better intuition for HTTP parsing than most developers.

References

- PortSwigger Web Security Academy – 0.CL lab

- James Kettle — HTTP Desync Attacks (PortSwigger research)

- RFC 7230 — HTTP/1.1 Message Syntax and Routing (for request framing details)