Lab: Blind SQL injection with conditional responses

Beginner-friendly, step-by-step walkthrough: exploit a blind SQL injection using boolean/conditional responses (TrackingId cookie). Includes exact payloads (placeholders), length discovery, character extraction with Burp Intruder, optimizations, detection recipes and developer-focused remediation.

⚠️ Disclaimer

This write-up is for educational and defensive purposes only. Perform these techniques only in legal, controlled environments such as PortSwigger Web Security Academy or your own testbeds. Do not use these techniques on systems you do not own or have explicit permission to test.

TL;DR (short summary)

This lab contains a blind SQL injection where the application queries the value of a tracking cookie. The application does not return query results or errors, but it displays a “Welcome back” message when the query returns any rows. We can use that boolean behavior to infer database truths.

High-level steps I followed:

- Confirm boolean-based injection by toggling a true/false condition in the

TrackingIdcookie. - Confirm

userstable andadministratoraccount exist by invoking boolean subqueries. - Discover the administrator password length by incrementing a

LENGTH(password) > Ncheck. - Extract password characters by testing

SUBSTRING(password, pos, 1) = 'x'for each position using Burp Intruder (cluster-bomb or multiple single-position attacks). - Use the recovered password to log in as administrator.

All proof-of-concept requests below use <LAB_HOST> and placeholder cookie prefixes. Never include real credentials or tokens in published posts.

1 - Why this lab matters (beginner explanation)

Blind SQL injection is when the application does not disclose query output or meaningful errors, but you can still infer data using side effects - here, the presence or absence of a specific banner (“Welcome back”) in the response. This is a core pentesting skill because many real applications hide error messages and still expose boolean differences, timings, or side effects that leak data.

In this lab the injection vector is a cookie (TrackingId), which is commonly used for analytics. Cookies are user-controllable and often forgotten during secure-coding reviews - making them a surprisingly useful attack surface.

2 - Initial reconnaissance: intercept the front page and find the cookie

I opened the lab homepage with Burp Proxy enabled and captured the front page request. The server and cookies looked like:

The important item is the TrackingId cookie. The app performs a SQL query using this value, so it’s a candidate for blind SQLi.

First manual test - boolean sanity check: I modified the cookie to test a trivial true/false condition.

In Burp Repeater I changed the cookie to:

Response: Welcome back appeared.

Then I sent:

Response: Welcome back did not appear.

This confirms the server evaluates our injected boolean expression, so we can learn true/false information by observing the Welcome back banner.

Important: Keep all other headers/cookies the same when testing to avoid false negatives (CSRF/session, etc.).

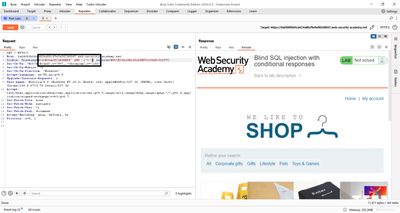

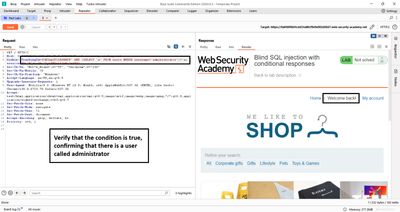

3 - Confirming the presence of users and administrator

Before extracting the password we need to confirm the users table and administrator row exist. With boolean blind SQLi you check for existential truth using subqueries.

Example checks I ran:

Both returned the Welcome back banner, confirming:

userstable exists and is readable by the DB user.- A row with

username='administrator'exists.

At this point we can safely focus on discovering the administrator password.

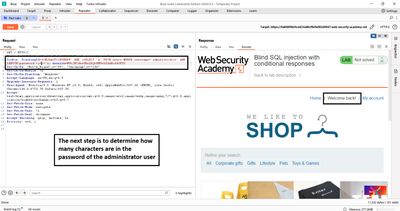

4 - Determining password length (why and how)

We need the password length before per-character extraction - it bounds our attack and reduces wasted requests. The approach is simple: ask boolean questions of the form LENGTH(password) > N.

Example requests (use Burp Repeater):

When the condition transitions from true (Welcome back shown) to false (no Welcome back) you’ve crossed the actual length.

I incremented N until the condition stopped returning true. In this lab the length was 20 characters.

Practical tip: You can speed this up with binary search (test >8, >16 etc.) if length may be large. For short lab passwords manual increment is fine and simpler.

5 - Character extraction strategy

Now we know there are 20 characters. To find each character, we test the value of SUBSTRING(password, position, 1) against possible characters. The lab hint limits characters to lowercase alphanumeric (a–z, 0–9), so our charset is small (36 characters) - perfect for automation with Burp Intruder.

Example test for position 1:

If the response shows Welcome back, the first character is a.

We repeat for position 1 with all possible characters until the response flips to true - that gives the correct character. Then increment position and repeat.

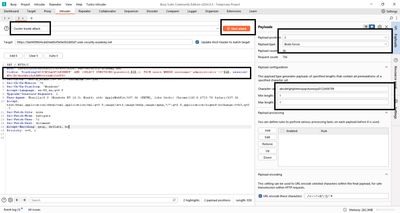

6 - Using Burp Intruder effectively (step-by-step)

Manual character-by-character probing is tedious. Burp Intruder automates the process. Here’s how I configured Intruder for this lab:

-

Send the intercepted front-page request to Intruder (right-click → Send to Intruder).

-

Set the payload position: In the

TrackingIdcookie value, replace the test character with payload markers around it:- The first marker (

§1§) is the position marker (I used a constant1and will change between runs). - The second marker (

§a§) is the character payload slot.

(Alternatively, you can use a single payload slot for characters and manually change the position between attacks.)

- The first marker (

-

Attack type: Use Cluster Bomb if you want to test multiple positions and characters in one run (two payload positions produce Cartesian product). For clarity and control I ran one position at a time using Simple list for characters - this yields easier interpretation of results.

-

Payload set: Under the Payloads tab, add

a–zand0–9(36 entries). Use "Add from list" or paste them. -

Grep the responses: Go to Settings → Grep - Match and add

Welcome back(exact phrase). This marks successful rows. -

Start the attack and watch results. The row where

Welcome backis ticked gives the character for that position.

Optimization tips:

- Set a short timeout and reasonable parallelism; avoid DoS on lab server.

- Use a unique marker per position if you run multiple positions in one attack to avoid confusion.

- For production pentests discuss rate/impact with operations - never run noisy attacks without coordination.

7 - Alternative improvements & optimizations

- Binary search on character ranges: Instead of testing every character, you can test if character > 'm' to cut the search space in half (works because character sets are ordered). This reduces requests per position from 36 to ~6 on average.

- Use ASCII ranges: Test

ASCII(SUBSTRING(...,1,1)) > 109(example) to perform binary search on ASCII code. - Use multi-position cluster bomb: Intruder can run two payload positions (position index and character set) to brute-force combinations, but the result set is large - I prefer single-position runs for clarity.

- Scripted automation: Tools like sqlmap can automate blind extraction using boolean payloads - useful for scale but be mindful of noise and authorization.

8 - Troubleshooting common pitfalls

| Problem | Likely cause | Fix / Advice |

|---|---|---|

| No difference between true/false requests | Missing or altered cookie/session; server-side caching | Ensure session/cookie state same; disable caching and repeat tests |

| Grep misses “Welcome back” | Different phrasing or HTML encoding | Inspect raw HTML (Ctrl+U) and update grep string; consider searching for a unique element |

| Intruder shows many 'true' rows | Payload encoding issues (URL encoding, quotes) | Use Repeater to verify single test; ensure payload markers are placed correctly and encoded as needed |

| Too slow | Large charset or long password | Use binary search or reduce charset; run single-position attacks rather than full permutations |

| App blocks requests | WAF/defense triggered | Slow rate, discuss with ops for authorized tests, or use less noisy techniques |

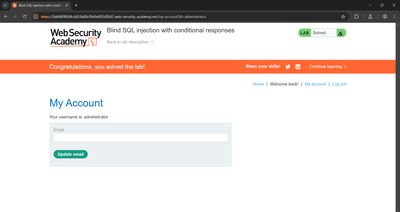

9 - Confirming success and logging in

After extracting all 20 characters I had the administrator password. I then used a standard login POST (placeholders):

The application accepted the credentials and displayed the admin dashboard / lab success banner. Capture a short screenshot for your report (redact full secrets in public reports).

Ethical note: For real engagements never include the raw password in public disclosure. Provide a redacted proof-of-concept and remediation steps.

10 - Defensive perspective (how to prevent blind SQLi)

This section is mandatory and must be actionable.

10.1 Code fixes (primary)

- Use parameterized queries and prepared statements. That eliminates injection vectors by treating inputs as data.

- Avoid dynamic SQL entirely for cookies and analytics inputs. Sanitize and validate any cookie values that reach DB queries.

10.2 Input validation & allow-listing

- Treat cookie values as untrusted: enforce a strict format (e.g., base64 token, UUID) and reject unexpected characters like quotes or SQL control chars.

- Map tokens to server-side identifiers rather than reusing the raw cookie value in SQL.

10.3 Reduce information leakage

-

Do not reveal conditional differences in responses that correlate with DB query results. In practice:

- Avoid showing special banners purely based on DB results for anonymous users.

- Make responses uniform for both success and failure where possible.

10.4 Database privileges & separation

- The DB account used for public pages should have minimal privileges: read-only on public tables only.

- Store sensitive user data under different schemas or with additional access controls.

10.5 Monitoring & detection

- Alert on suspicious cookie values containing quotes,

AND,SELECT, or other SQL keywords. - Detect repeated parameter permutations from the same IP (column probing / character extraction patterns).

- Rate-limit requests per IP to slow down automated extraction.

10.6 Testing & CI

- Add automated tests that attempt simple boolean probes against cookies and endpoints in staging. Fail build if injection is possible.

11 - Real-world examples (impact & why defenders should care)

- Credential theft: Blind SQLi has been used to extract admin or API credentials from systems that hide error messages, enabling account takeover.

- Long-term exfiltration: Because blind extraction is low-noise, attackers can exfiltrate large datasets slowly to avoid detection.

- Chained attacks: Extracted credentials or schema names can help attackers pivot to internal systems or craft targeted social-engineering campaigns.

Real incidents repeatedly show that silent vulnerabilities (like blind SQLi) are just as dangerous as noisy ones - they just require more persistence.

12 - Reporting and remediation workflow (for teams)

When you find blind SQLi:

- Document reproducible steps (request, exact cookie injection pattern, indicators).

- Avoid sharing raw secrets in public bug reports - redact or provide screenshots with redaction.

- Suggest prioritized fixes: parameterize queries, input validation, privilege separation.

- Coordinate fixes with ops: rotate any secrets that may have been exposed and re-run tests after patching.

- Add monitoring for similar probes (cookie-based injections).

13 - Wrap-up & final thoughts

Blind SQL injection via conditional responses is a classic yet powerful vulnerability. It teaches important concepts: moving from detection to inference, bounding queries, and automating safe extraction. The defensive fixes are simple and effective - parameterize queries, validate inputs, and reduce the information attackers can observe.

References & further reading

- PortSwigger Web Security Academy - Blind SQL injection labs.

- OWASP - SQL Injection Prevention Cheat Sheet.

- Burp Suite documentation - Intruder configuration and Grep match features.

- Articles on boolean-based blind SQLi and optimizations (binary search, ASCII comparisons).