Lab: SQL injection UNION attack - finding a column containing text

Step-by-step walkthrough: use a UNION-based SQL injection to find a column that accepts text. Beginner-friendly lab writeup with exact payloads (placeholders), troubleshooting, defenses and real-world context.

⚠️ Disclaimer

This write-up is strictly for educational and defensive purposes. Perform these techniques only in legal, controlled environments such as PortSwigger Web Security Academy or your own test systems. Do not attempt attacks on systems you do not own or have explicit permission to test.

TL;DR

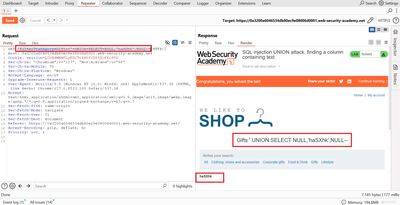

This lab asks you to find a column in the application's query result that accepts and displays string data. After confirming the query returns three columns (from the previous lab), I tested each column by replacing a NULL with the lab-provided random string haSXhk until it appeared in the page. The exact payload that solved the lab was:

This walkthrough explains the reasoning and step-by-step method, shows how to troubleshoot common pitfalls, covers detection and defensive controls, and gives real-world context so the technique is meaningful beyond the lab environment.

If you missed the column-count step, review the "UNION column counting" exercise first - finding the number of columns is prerequisite to this lab.

1 - Lab goal & overview

Lab goal (PortSwigger): Use a UNION-based SQL injection to return an extra row containing the random value the lab provides (haSXhk) so that the injected value is visible in the application response. This confirms which column accepts and renders string data.

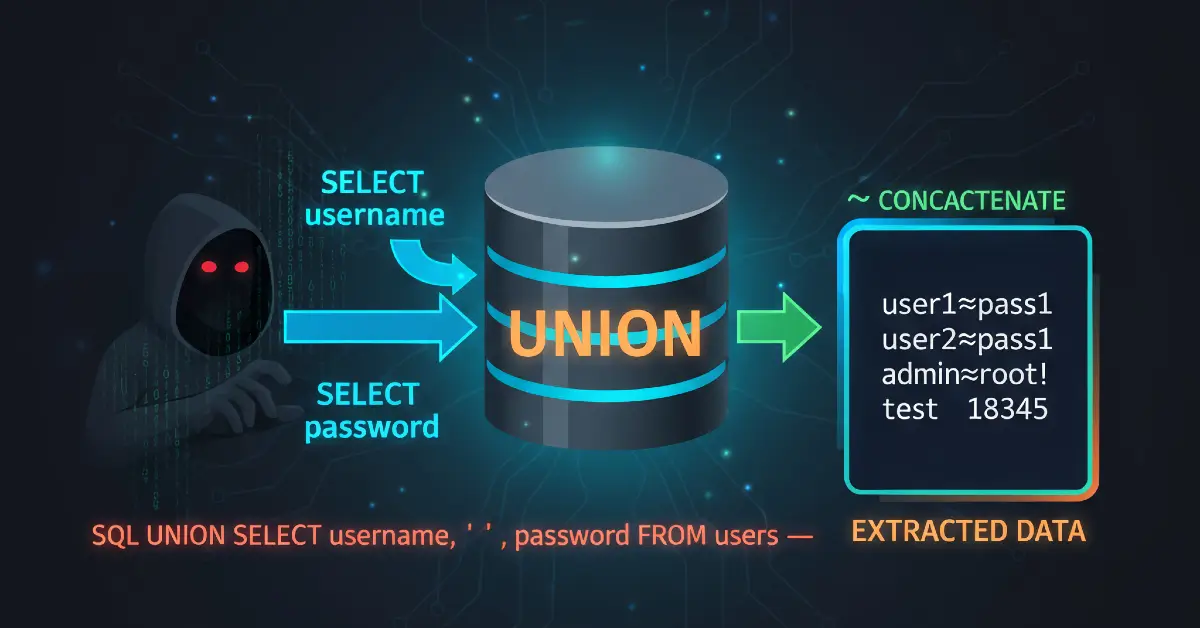

Why this matters: UNION requires both queries to return the same number of columns and compatible types. Knowing a text-capable column lets you return arbitrary strings (and later, extract database values) through that position. This is a controlled, methodical step toward safe data extraction in an authorized assessment.

2 - Recon: capture the filter request

I proxied my browser through Burp and navigated to the product listing page. The filter parameter controls which category is shown. A sanitized example request looked like this:

This confirmed a classic injection surface - a textual parameter used directly in a database query. Because the page renders query results in the response, it's a good candidate for a UNION probe.

3 - Quick recap: ensure you already know the column count

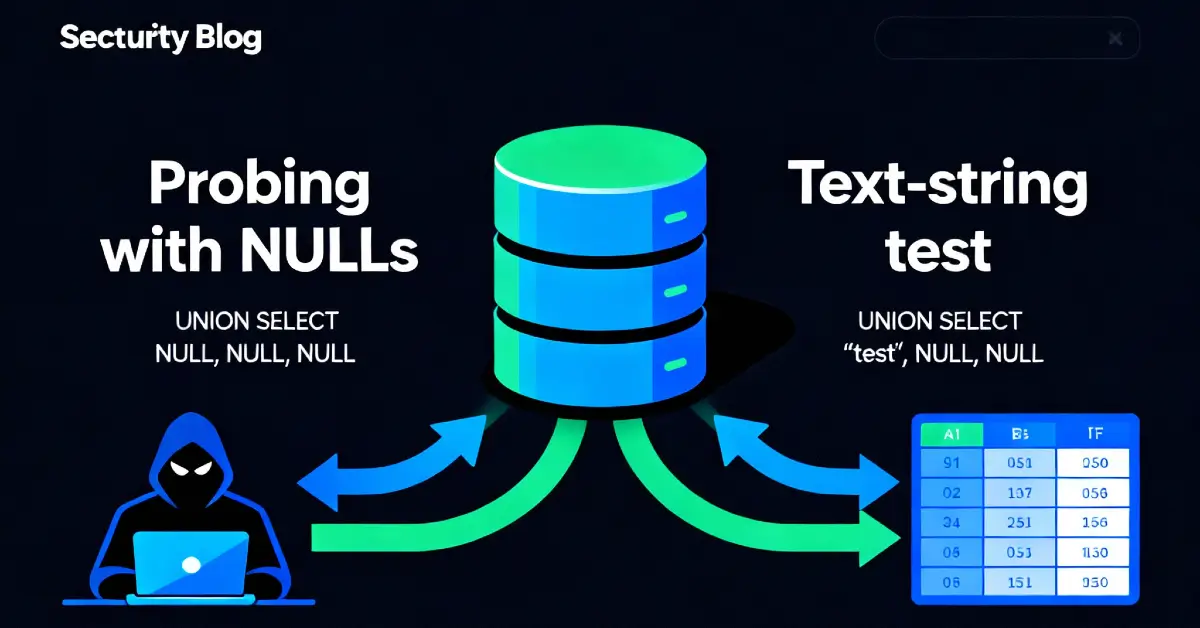

This lab assumes you’ve already determined the original query returns three columns (from the previous lab). If you haven’t, the first step is to issue UNION SELECT NULL probes with incremental NULLs until the server accepts the union. Example that confirmed three columns in the prior lab:

If that previously succeeded for you, proceed. If not, repeat the column-counting step first - UNION requires matching column counts.

4 - Strategy: how to find a text-capable column

The approach is straightforward:

- Use the confirmed

UNION SELECTstructure with the correct number ofNULLs. - Replace each

NULLone at a time with the lab-provided random string (haSXhk) - each replacement tests whether that column is rendered as text. - Send the request and inspect the response HTML for the random string.

- When the string appears, you’ve identified a text-capable column.

Concretely, with 3 columns you test these variants (URL-encoded when using a browser):

One of these will reflect haSXhk into the response when it hits a column printed into the template.

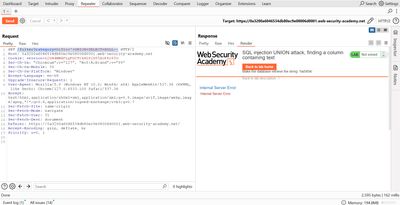

5 - Exact payload used in this lab (what solved it)

In this particular lab the server reflected the random string when it was placed in the second column. The successful payload was:

Once that request was sent, the page contained haSXhk (visible in the HTML). At that moment you know:

- The original query returns 3 columns.

- The second column is text-capable and rendered on the page.

6 - Why this works (technical explanation)

UNION combines the result sets of two SELECT statements. For UNION to succeed:

- Both SELECTs must return the same number of columns.

- Each corresponding column should be a compatible type for the DB to combine them.

We use NULL as a neutral placeholder to satisfy the column count without forcing a type. Replacing a NULL with 'haSXhk' tests if that position is rendered as text. If the application template echoes that column into the HTML (product name, description, etc.), the injected string will be visible.

Important nuance: HTML rendering can escape or transform values. If the string does not appear but the request succeeded, search the raw HTML source or try a distinct token like UNIQ123 to find hidden echoes.

7 - Troubleshooting common issues

Even simple labs can mislead you. Here are the common problems and fixes I used:

- No visible injected string but no error: The union succeeded but the injected row isn't output where you expected. Inspect full HTML or try placing the test string in other columns.

- Parameter inserted inside quotes in the original query: Make sure your injected payload correctly terminates the surrounding quote. In many labs the pattern

Gifts+'+UNION+SELECT+...--is used to close the literal and append the union. - WAF or filtering blocking

UNIONorSELECT: In labs you’re typically allowed to use these, but on real targets you may need to test variants - or better, stick to authorized labs. - Encoding / URL escaping: When testing in a browser, use URL-encoded payloads (space as

+or%20,'as%27), or use Burp Repeater to avoid encoding issues. - Type mismatch after replacing

NULL: Rare in this stage, but if you get type errors, consider trying a cast (advanced) or test other columns. - Line-ending comment requirements: Some DBMSs require

--(dash-dash-space) for comments; try with and without a trailing space if you see odd behavior.

Practical tip: Use a short, unique test string (the lab provided haSXhk is ideal). It prevents false matches and speeds up verification.

8 - Confirming the find & what to do next

Once haSXhk appears in the response:

- Note which column index (1, 2, or 3) showed the string.

- That column is now your text sink - you can use it to return arbitrary strings from other tables (in lab contexts), or to test data extraction payloads safely and responsibly.

- As a practice step, you can replace the test string with a predictable database expression (e.g.,

database()orversion()in some DBs) to see DB info, but only in labs.

Example extraction payloads (lab-only) after finding a text column at position 2:

Always limit the scale of extraction in any environment to avoid noisy or damaging behavior.

9 - Defensive perspective (how to prevent this)

Finding a text-capable column is useful for attackers - defenders can stop it with these actions:

9.1 Parameterize queries & avoid string concatenation

- Use prepared statements or an ORM that separates code from data. Never interpolate user values into raw SQL.

9.2 Map inputs to internal IDs

- Instead of passing raw category names to SQL, map them to internal numeric IDs or use a safe enum. Example:

category_id = 5instead ofcategory='Gifts'.

9.3 Whitelist allowed values

- If categories are a finite list, validate the input against that allowed list server-side.

9.4 Hide DB errors & reduce information leakage

- Don't expose database error messages to users. Generic error pages make enumeration harder.

9.5 Limit DB privileges

- The web app’s DB account should have the minimum SELECT privileges required. If possible, avoid exposing sensitive tables to the same account used by public pages.

9.6 WAF & detection rules

- Flag requests that contain

UNION SELECT NULLor unusual comma-separatedNULLpatterns in short parameters. - Set alerts for repeated

NULLprobes from the same source.

9.7 Security tests in CI/CD

- Add automated checks that run

UNION SELECT NULLprobes against staging filters to detect column-count mismatches or unsafe dynamic SQL.

10 - Detection & logging recipes (practical SIEM alerts)

- WAF rules: Alert when

categoryor other filter parameters containUNION,SELECT, or repeatedly containNULLsequences. - SIEM correlation: Trigger if a single IP sends multiple

NULL-probe requests within a short window and receives errors or unusual responses. - Application logs: Record parameter values for failing queries - flag when values contain SQL control keywords.

- Behavioral alerts: If normally static filter pages start showing injected content during scans, investigate source IPs and block if malicious.

These recipes are defense-in-depth - they supplement, not replace, secure coding.

11 - Real-world examples & impact

Finding a text column is often the gateway to data extraction in real incidents:

Example 1 - Sensitive metadata leak

An online catalog used concatenated filters. Attackers discovered a text-capable column and extracted vendor notes revealing API keys. Attackers used those keys to query internal services.

Example 2 - Aggregated product scraping

A marketplace suffered from automated attackers who enumerated column counts across category filters and then harvested product metadata for competitive intelligence. The root cause: unchecked filter parameters and over-privileged DB access.

Example 3 - Chain to deeper compromise

In another organization, column enumeration led to discovering a column referencing admin emails. Attackers used those to conduct targeted phishing and later used leaked credentials to breach additional systems.

These examples show the stepwise nature of attacks: reconnaissance → column enumeration → extraction → pivot. Stopping the early steps is often the most cost-effective defense.

12 - Practice suggestions (how to learn faster)

- Repeat this lab until you can do the

NULL-probe and text replacement quickly and reliably. - Practice with slightly different templates (GET vs POST, parameters inside quotes, parameters inside JSON) to see how injection context affects payload shape.

- Build a tiny local app that concatenates filter values and practice fixing it by introducing prepared statements and whitelisting. The "before and after" code makes the lesson stick.

13 - Wrap-up & final thoughts

This lab is focused but fundamental - it teaches a repeatable technique that opens the door to data extraction in SQLi scenarios. The workflow is:

- Confirm column count with

NULLprobes. - Replace

NULLslots with a unique string (haSXhk) to find a text-capable column. - Use that column as a sink to return strings from other tables - always in lab/authorized contexts.

- Defend with parameterized queries, whitelisting, least privilege, and detection.

References & further reading

- PortSwigger Web Security Academy - SQL Injection (UNION) labs.

- OWASP - SQL Injection Prevention Cheat Sheet.

- Database vendor docs for SQL syntax and casting (useful for advanced payloads).