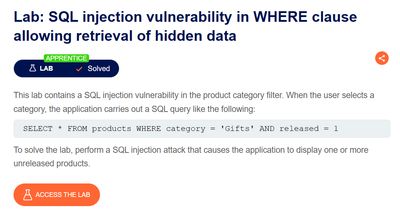

Lab: SQL injection vulnerability in WHERE clause allowing retrieval of hidden data

Beginner-friendly, expert-grade walkthrough for the PortSwigger lab: SQL injection vulnerability in a WHERE clause allowing retrieval of hidden data. Step-by-step with payloads, explanations, real-world examples, and defensive advice.

⚠️ Disclaimer

This write-up is for educational purposes only. It is designed for legal, controlled environments such as PortSwigger’s Web Security Academy. Do not attempt these techniques on any system without proper authorization.

1 - Introduction

When I started the SQL injection learning path on PortSwigger’s Web Security Academy, the very first lab was titled:

“SQL injection vulnerability in WHERE clause allowing retrieval of hidden data.”

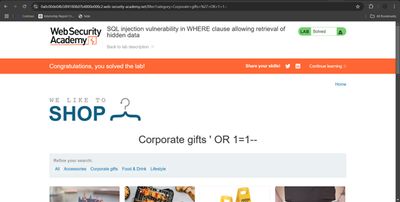

The goal sounded simple: the website hides certain products, and my job was to manipulate the WHERE clause of the SQL query so those hidden items show up.

This lab is a classic warm-up for SQLi. It doesn’t require advanced tricks like multi-stage UNION attacks or blind timing queries. Instead, it teaches the core principle:

➡️ If user input goes directly into a WHERE clause without sanitization, you can reshape the condition and reveal everything.

That’s exactly what I did in this walkthrough.

2 - Understanding the Lab Setup

The application provided by PortSwigger had a /filter endpoint, which allowed me to filter products by category. For example, a normal request looked like this:

This parameter is directly tied to the SQL query on the back-end. Something like:

At first glance, it only shows products inside “Corporate gifts.” But if that parameter isn’t properly protected, I could escape the query and add my own logic.

Beginner breakout: What’s a WHERE clause?

A WHERE clause tells the database which rows to return. Example:

This query only returns users with role = admin. If an attacker can change 'admin' into 'admin' OR 1=1, suddenly the condition is always true and all rows return.

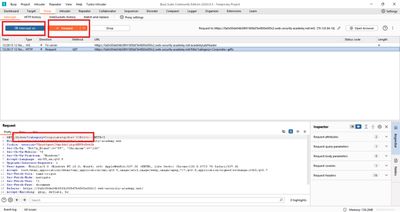

3 - Recon: Finding the Injection Point

My first step was to capture the request in Burp Suite Proxy. I clicked a few categories and quickly saw how the parameter changed in the URL.

When I sent the request to Repeater, I noticed that I could freely edit the category value.

So I tested with the classic boolean payload:

What happened?

✔️ Suddenly, the page showed all products, not just “Corporate gifts.”

That was my confirmation: the input was being placed directly into a SQL WHERE clause, and my injection worked.

4 - Why That Payload Worked

Let’s break it down:

The normal query looked like this:

After my injection:

' OR 1=1makes the condition always true.--tells SQL to ignore the rest of the line (a comment).

Result: the database returns every product, including the hidden ones.

Beginner breakout: Comments in SQL

--starts a comment in many SQL dialects. Everything after it is ignored.- Some databases also support

/* ... */comments. - Attackers often use these to “cut off” unwanted query parts.

5 - Trying Variations (Why Not This Step?)

Whenever I solve labs, I don’t stop after the first success. I test small variations to better understand how the app behaves:

- Test 1:

✅ Returned no results (because the condition was false).

➡️ Confirms my injection really affects the logic.

- Test 2:

✅ Still returned all results.

➡️ Confirms the database treats quotes normally and is string-based.

Why this matters: By running these variations, I make sure the vulnerability is real and reliable, not just a coincidence.

6 - Real-Life Examples of This Weakness

SQL injection might feel like a classroom exercise, but history shows it has caused some of the largest breaches ever recorded. Even something as basic as manipulating a WHERE clause with OR 1=1 can have devastating consequences.

Example 1 - Login Bypass Attacks

In the early 2000s, attackers frequently bypassed login forms using exactly the same trick we used in this lab. A vulnerable application might check credentials like this:

If an attacker entered admin' OR 1=1-- as the username, the query became:

The condition OR 1=1 is always true, so the database returned the first user in the table - often the administrator. This trick was so common that it became part of pop culture references about “hacking logins.”

Example 2 - E-Commerce Sites Leaking Hidden Products

Real-world e-commerce platforms have accidentally exposed hidden, unreleased, or discounted products because of vulnerable product filters. Just like this lab, attackers tweaked category filters in the URL:

Instead of only returning visible items, the site dumped all products, including those not meant for customers (such as upcoming product launches or staff-only items). Even worse, some attackers discovered categories containing system data or staging items that should never have been public.

Example 3 - Search Boxes in Government Websites

Public-sector websites have also been found with SQLi in search forms. For example, a city portal might let users search for "business licenses" with queries like:

If unsanitized, a malicious input such as:

would turn the query into:

The condition always evaluates to true, returning all records in the database. In real incidents, researchers discovered sensitive citizen records exposed through nothing more than a simple OR condition.

Example 4 - The Famous Sony Pictures Hack (2011)

While the Sony hack involved multiple attack vectors, investigators confirmed that SQL injection was one of the entry points. Attackers reportedly used simple injection payloads to enumerate backend tables and pull out millions of user records. The breach exposed names, passwords, addresses, and more - showing how even "small" injections can scale to catastrophic data loss.

Takeaway:

This lab isn't just academic. The same OR 1=1 that revealed hidden products in PortSwigger's demo has been used to:

- Log in as admins.

- Leak unreleased items.

- Dump entire government datasets.

- Breach corporations worth billions.

It's a powerful reminder that "easy" SQLi is deadly in production.

7 - Extracting More with UNION (Lab-Level Expansion)

Although the lab was solvable with just OR 1=1, I also tested how to extract specific hidden values.

That's where UNION SELECT comes in. It lets me combine results from my own query with the original one.

Step 1 - Find number of columns

When the query stopped erroring at 3 columns, I knew the product table had 3 columns.

Step 2 - Find text column

When "TEST" appeared in the page, I knew the first column could display strings.

Step 3 - Return secret

If there was a hidden flag like "t46tDZ," I could place it there:

8 - Troubleshooting

Not everything works on the first try. I hit a few common bumps:

- Wrong number of columns: The server gave "column mismatch" errors until I found the correct count.

- Type errors: Sometimes I tried to inject a string into a numeric column. Using

NULLsolved it. - Encoding issues: Always URL-encode payloads (

'→%27, spaces →%20) to avoid browser mangling.

Beginner breakout: URL encoding

When sending payloads in URLs, browsers convert special characters. Example:

- Space →

%20 - Single quote

'→%27 --→%2D%2D

Always check if Burp is sending raw payloads correctly.

9 - Defensive Perspective (Most Important)

Now the big question: how do developers stop this?

1. Use Prepared Statements

Instead of building SQL with string concatenation, bind variables properly:

PHP (PDO):

Python (psycopg2):

This makes injection impossible, because the database never sees raw concatenated input.

2. Whitelist Inputs

If categories are fixed (like "Corporate gifts" or "Stationery"), enforce a dropdown and validate against allowed values.

3. Least Privilege

Use a database account with minimal privileges - no schema modification, no system access.

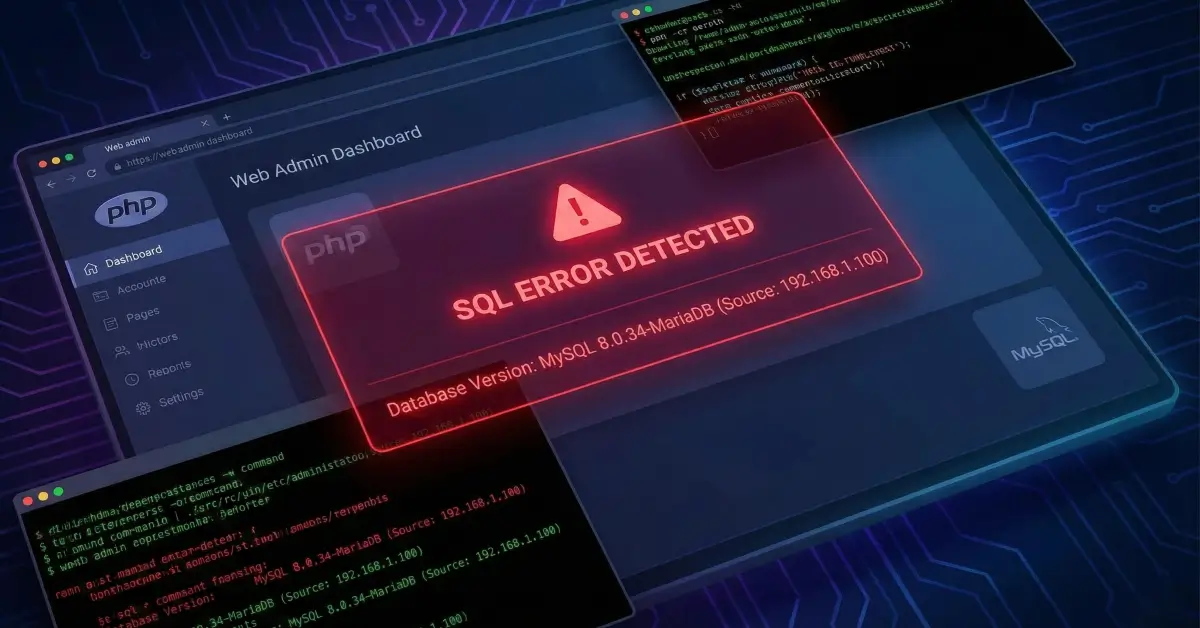

4. Error Handling

Don't show raw SQL errors to users. Attackers rely on error messages to refine payloads.

5. Automated Testing

Add SQL injection checks in your CI pipeline. Tools like sqlmap or custom test cases can reveal unsafe query building.

10 - Final Thoughts

This first lab in the SQLi path reinforced some key lessons:

- SQL injection often starts with something simple - just breaking out of a

WHEREclause. - The classic

OR 1=1--is still one of the fastest ways to confirm a vulnerability. - Even at this level, I can expand into UNION-based extraction to grab hidden values.

- In real life, the same weakness appears in filters, search bars, and logins.

- And the only true fix is parameterized queries.

For me, the highlight of this lab was watching the page transform - from showing only "Corporate gifts" to suddenly dumping all products. That "aha" moment is why SQL injection is such a powerful lesson for beginners.