How Changing a Single Number Exposed an Entire User Database (An IDOR Story)

A real-world breakdown of an IDOR vulnerability that escalated from a simple user ID change to full admin data exposure. Learn how it happened, why it worked, and how to prevent it.

Disclaimer (Educational Purpose Only)

This article retells a real-world security researcher’s authorized finding for educational and defensive learning.

The objective is to help developers, pentesters, and product teams understand how an Insecure Direct Object Reference (IDOR) can escalate to a full data breach - and how to prevent it responsibly.

Do not test or reproduce such findings on live systems without permission.

🧩 Introduction

Sometimes, the biggest discoveries come from the smallest mistakes - like typing one wrong number.

That’s exactly what happened to a researcher who stumbled upon a critical Insecure Direct Object Reference (IDOR) vulnerability in a fintech platform we’ll call CoinFlow.

It started as a harmless curiosity: changing a user_id value in an API request.

But it ended with access to over 50,000 user records, including admin reports and sensitive PII.

In this article, we’ll explore how that one parameter became the master key to an entire company’s data - and how to defend against this in real-world web applications.

Act 1: The “Boring” API That Wasn’t 🕵️♂️

Every great bug bounty story starts the same way: boredom, caffeine, and curiosity.

The researcher was testing CoinFlow, a financial management startup with a public API. Reconnaissance was thorough - a mix of automation and manual sleuthing.

Recon Symphony

Most endpoints were predictable:

/user/profile, /api/version, /status/healthcheck.

But one stood out:

“Transaction sequences”? “Analytics export”?

That endpoint smelled like complexity - and where there’s complexity, there’s often broken authorization logic.

When accessed directly, the server returned a 401 Unauthorized, which was expected.

After logging in as a test user (testuser_123), the researcher captured the request in Burp Suite:

The response was a clean PDF report of the user’s transaction analytics.

Everything looked normal… until one small detail caught the eye:

user_id=21745

And curiosity whispered: “What if I change that number?”

Act 2: From “No Way” to “Oh My God” - The IDOR Cascade 🎰

Changing 21745 to 21746 should have triggered a permission error.

Instead, it unlocked another user’s report.

Payload 1: Simple Increment Test

Result: Full PDF report of another user.

Impact: Horizontal privilege escalation - one user accessing another’s data.

But that was just the beginning.

Step 2: Horizontal Escalation Confirmed

To verify it wasn’t a caching fluke, the researcher created a second test account (testuser_456) with ID 22891.

Logged back in as testuser_123, they accessed:

It worked again.

This confirmed broken access control across users - a textbook IDOR.

Step 3: The Vertical Escalation (Finding Admin IDs)

If user IDs were sequential, admin IDs might be too.

So began the fuzzing phase:

Result:

user_id=10000 didn’t just return any report - it returned:

“System Administrator Quarterly Transaction Analysis”

💥 Jackpot. The researcher had accessed admin-level financial analytics.

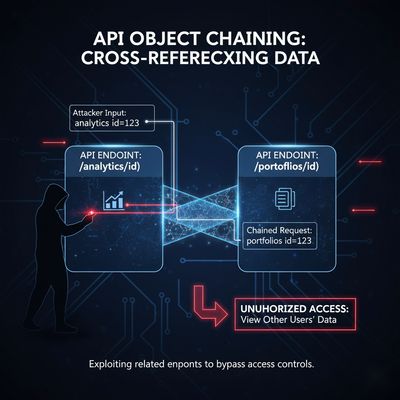

Act 3: The Plot Twist - Chaining Parameters 🔄

The real brilliance came next - a method the researcher called “Parameter Chaining” or “Object Bridging.”

Inside the admin PDF, there was a field called:

These looked like portfolio IDs, not just random numbers.

Using recon data, the researcher found another API endpoint that referenced portfolios:

Naturally, the next step was to connect the two.

Payload 3: Object Bridging Attack

Response:

By chaining an IDOR from the analytics endpoint with a second insecure endpoint, the researcher dumped every user linked to the admin portfolio - including their emails and roles.

This was no longer “view one unauthorized report.”

This was total data exposure.

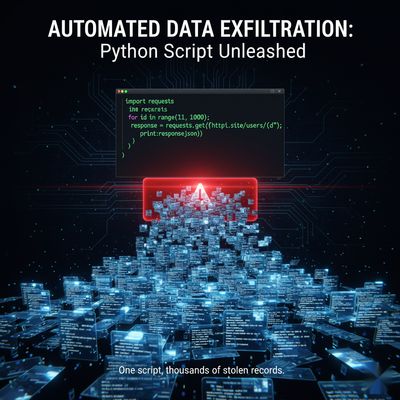

Act 4: Automating the Apocalypse 🤖

At this point, automation became inevitable.

The researcher built a small Python PoC to demonstrate the attack chain.

Proof of Concept (Defensive Illustration)

The result?

A full export of 50,000+ user records across multiple portfolios, including admin accounts.

Act 5: The Payday and The Patch 💰

The researcher responsibly reported:

- The base IDOR in

/analytics/export - Vertical privilege escalation via sequential IDs

- The chained exposure across portfolio endpoints

Within hours, CoinFlow triggered their incident response plan, locked down all endpoints, and implemented layered authorization.

The Fix Included:

- ✅ Authorization middleware on every API route

- ✅ UUID-based object identifiers instead of sequential integers

- ✅ Role-based access validation for portfolio queries

- ✅ Audit logs and rate limiting for sensitive endpoints

The bounty? $5,000 for a single number change.

Defensive Deep Dive: Why It Happened (and How to Prevent It)

This case wasn’t just luck - it revealed common systemic issues in API security.

Root Cause Breakdown

| Weakness | Description | Risk |

|---|---|---|

| Missing authorization layer | API didn’t validate if user_id matched session identity |

Cross-user data access |

| Predictable object IDs | Sequential numeric IDs enabled easy enumeration | Horizontal & vertical IDOR |

| Shared object references | Admin data leaked other privileged IDs | Chaining to larger exposure |

| No data scoping | Endpoints didn’t enforce “least privilege” | Global exposure through one token |

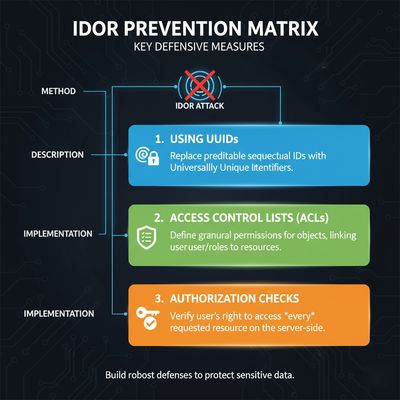

Defensive Engineering Blueprint 🧱

To defend your APIs from similar “master key” flaws, implement the following controls:

🔐 1. Enforce Server-Side Authorization

Validate who is requesting what on every object-level request:

🧩 2. Use Non-Predictable Identifiers

Replace integers with UUIDs or hashed keys:

This alone kills most enumeration-based IDORs.

⚙️ 3. Implement Object-Level ACLs

Every object (portfolio, transaction, user report) should have a scope list:

🚦 4. Add Rate Limiting & Logging

Detect automated scraping or fuzzing:

Monitor logs for suspicious sequential requests.

🧱 5. Adopt Zero-Trust APIs

Treat every endpoint as untrusted - even if internal.

Authenticate every request, validate every parameter, and assume nothing.

Troubleshooting & Pitfalls

❌ Mistake 1: “We Use JWT, So We’re Safe.”

Authorization != Authentication.

JWT ensures the user is logged in - not that they’re authorized for the resource.

❌ Mistake 2: “It’s Internal API, Not Public.”

Most breaches start internally.

Treat internal APIs as public-facing from a security design perspective.

❌ Mistake 3: “We Use Obscure IDs.”

Obscurity isn’t security. Even long numeric IDs can be guessed.

✅ Solution:

Strong authorization checks + UUIDs + logging.

No shortcuts.

Real-World Parallels

This bug isn’t isolated. IDOR is consistently the #1 OWASP vulnerability under Broken Access Control.

Notable Industry Cases

- Facebook (2020) – An exposed object ID let attackers fetch private photos.

- Instagram (2021) – IDOR in GraphQL endpoint revealed hidden posts.

- Tesla (2022) – Vehicle telematics API allowed cross-user data queries.

These reinforce one lesson:

Authorization must be explicit - never implied.

Step-by-Step Prevention Checklist ✅

| Step | Defense Mechanism | Example |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Verify object ownership | Check request.user_id == object.user_id |

| 2 | Use UUIDs | uuid4() instead of incremental IDs |

| 3 | Implement RBAC | Assign roles and enforce permissions |

| 4 | Validate indirect references | Map indirect IDs to authenticated users |

| 5 | Secure API endpoints | Lock down all /v1 and /v2 routes |

| 6 | Log every 403 | Investigate authorization rejections |

| 7 | Review third-party integrations | Least privilege across microservices |

Defensive Perspective Summary

- IDORs aren’t just minor bugs - they’re data breaches waiting to happen.

- Sequential IDs = predictable pathways for exploitation.

- Always enforce object-level authorization across every API function.

- Security isn’t about adding WAFs; it’s about designing with least privilege from day one.

Final Thoughts

This entire story began with a single digit - changing 21745 to 21746.

But beneath that one number lay an architectural flaw: a missing authorization check.

That’s the nature of modern vulnerabilities - small oversights, massive consequences.

For developers:

Build APIs with least privilege and explicit validation.

For security researchers:

Keep exploring responsibly. Every “boring” endpoint might hide a master key.