Burp MCP DNS Rebinding: local APIs as a remote SSRF vector (researcher case study)

A defensive case study of a DNS-rebinding attack that abused a local Burp MCP API to perform SSRF-like requests from the victim machine. Learn why local APIs change the threat model, how to detect this class of issue, and hardened mitigations for product teams.

Disclaimer (mandatory): This article summarizes a responsibly disclosed third-party research report about an issue involving local developer tooling. It focuses on root causes, detection, and mitigations. It intentionally avoids step-by-step exploit code. Use the guidance to harden your tools and test only systems you own or are authorized to test.

TL;DR

A researcher found that Burp's MCP (Model Context Protocol) server exposed powerful request-making functionality on a localhost debugging port. Because the MCP API accepted calls from browser contexts without strict origin/CORS checks and performed arbitrary outbound HTTP requests, a DNS-rebinding style web page could coax a victim's browser into instructing the local MCP server to fetch internal resources (cloud metadata, internal dashboards) - effectively turning the victim's Burp instance into an SSRF proxy. Vendor triage and a coordinated fix resulted in a $2,000 bounty for the researcher. The real takeaway: local APIs are part of your attack surface and must be defended accordingly.

Why this is important

Modern developer tooling frequently exposes local HTTP/WebSocket endpoints to enable IDE integrations, browser debugging, or automation. These endpoints are extremely convenient - but convenience changes your trust model:

- Tools running on

localhostoften assume "local = trusted". Attackers can leverage the browser and network tricks to get around that assumption. - Features that let local tooling issue arbitrary requests (e.g., "send_http1_request") are SSRF primitives if influenced by untrusted callers.

- DNS rebinding and similar techniques can cause the browser to treat a remote hostname as same-origin while resolving it to a local IP - enabling cross-origin calls that the local API may not expect.

When local automation APIs are permissive, the impact can be severe: sensitive metadata, internal configuration, and otherwise-inaccessible services become reachable from the open web via a victim's machine.

High-level summary of the vulnerability

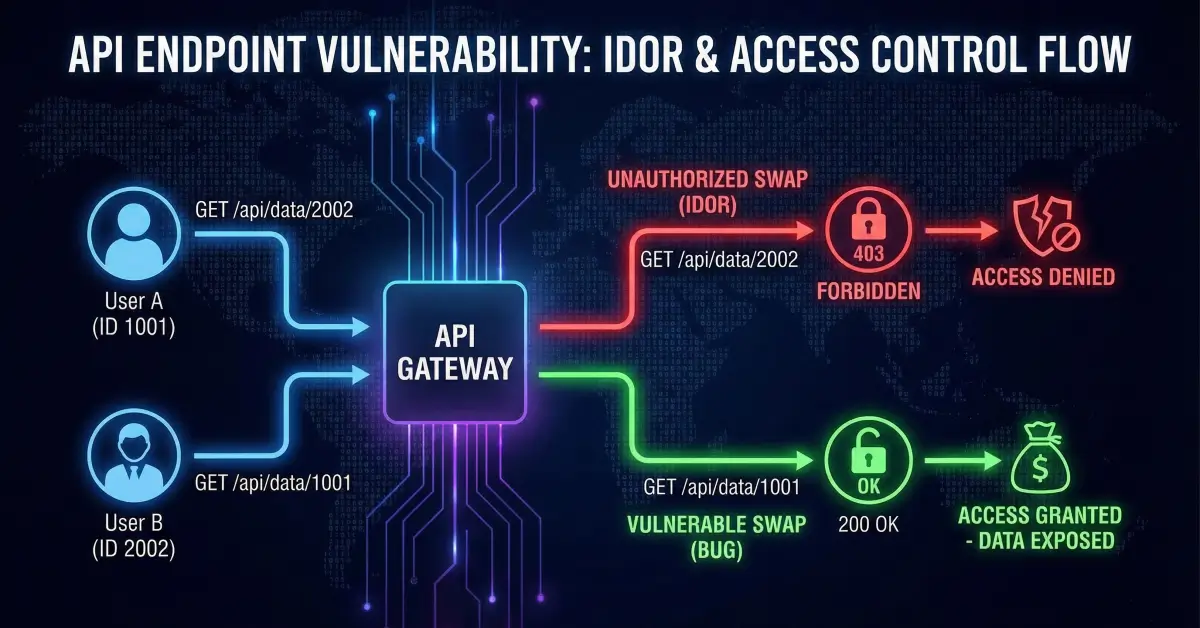

This is the conceptual flow (defensive, non-exploit):

- Burp's MCP server listens on a loopback port on the user’s machine and offers endpoints such as

send_http1_request. - The MCP API did not perform strict origin validation or required interactive authorization for powerful operations.

- A malicious web page loaded in the victim's browser used DNS rebinding or similar techniques to make the browser believe the remote page and the local MCP service were same-origin.

- The web page called MCP endpoints via the browser; MCP performed outbound requests (e.g., to

http://169.254.169.254) and returned responses which the page exfiltrated. - The attacker gained access to internal-only data (metadata, admin UIs), using the victim machine as an SSRF proxy.

Again: this is conceptual to explain the root cause and mitigation. The vulnerability is not merely "rebinding works" - it is the combination of a local powerful API + absent/weak origin checks + ability to issue arbitrary outbound requests.

The core engineering mistakes (root causes)

The issue arises when multiple failures line up:

- Implicit trust of loopback: trusting connections from

127.0.0.1as equivalent to "trusted, local developer". - Missing origin validation: accepting browser-originated requests to sensitive endpoints without verifying

Originor requiring user consent. - Large capability surface: exposing endpoints capable of arbitrary HTTP operations (method, headers, body, target host).

- No explicit user confirmation: no UI handshake to confirm high-risk actions requested by external clients.

- Default, permissive configuration: shipping defaults that allow remote automation without strict ACLs.

Fixing one alone reduces risk; fixing many provides defense-in-depth.

Detection & auditing checklist (for product teams)

Use this checklist to surface similar issues in your tooling and product suites. These checks are defensive and safe to run in controlled environments.

| Audit step | What to look for | Why it's important |

|---|---|---|

| Local HTTP APIs inventory | Scan developer machines for listeners on loopback ports (common: 9222, 9229, 9876, 3000). | Discover hidden service endpoints. |

| Exposed functionality mapping | Identify endpoints that accept a url, host, or path parameter and perform outbound requests. |

Such endpoints are SSRF primitives. |

| Origin / CORS checks | From a browser, attempt cross-origin fetch() to local endpoints and inspect Access-Control-Allow-* headers. |

Permissive CORS indicates risk. |

| Authentication model | See if endpoints require a session token, client cert, or UI confirmation. | Unauthenticated powerful endpoints are dangerous. |

| CI/packaging defaults | Review shipping defaults that enable remote debug features. | Default-on features expand the blast radius. |

| Logging & anomalous behavior | Check logs for inbound origins and suspicious sequences (web request followed quickly by outbound request to internal IPs). | Useful for post-compromise detection. |

Practical mitigations (engineering guidance)

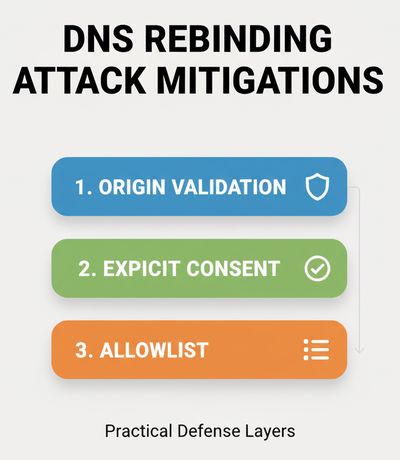

Mitigations must be layered - treat the problem like a capability-abuse risk. Below are prioritized, concrete measures.

1) Strict Origin & CORS validation

If your local API is callable from the browser, validate the Origin header against an explicit whitelist. Reject requests that do not match a known, allowed origin. Avoid Access-Control-Allow-Origin: * for any powerful endpoints.

2) Require explicit, interactive user consent

For actions that perform external network requests or handle secrets, require a user-driven flow in the trusted UI (a modal prompt) that verifies the request and records consent. "Silent" acceptance is dangerous.

3) Strong authentication for remote automation

Prefer per-user, machine-bound tokens or mTLS rather than relying on "localhost is trusted." For example, issue a long-lived credential that the product UI can provision (and revoke) and bind it to OS-level user context.

4) Capability restriction & allowlists

If you must expose a request API, restrict targets: maintain an explicit allowlist, deny link-local and metadata IP ranges (169.254.169.254, 169.254.169.253, 169.254.170.2, etc.), and refuse private network ranges by default. Limit permissible HTTP methods and headers.

5) Least privilege defaults

Ship with debug and remote-integration features disabled by default. Require explicit revocation/enablement by knowledgeable users.

6) Process-level protections

Consider binding debug sockets to the owner user only (use user-scoped Unix sockets) or require OS-level permissions to connect.

7) Rate limits & anomaly detection

Limit the number of outbound requests per minute a local API can initiate and alert when the pattern looks like automation triggered by a webpage.

8) Logging & redaction

Log full request context for audit, but redact sensitive payloads. Emit alerts for unusual origin + destination patterns.

Safe design patterns: verification pseudocode

Below is a defensive pseudocode sketch showing how a local API should validate inbound browser requests before performing an outbound fetch. This demonstrates what to do - not how to attack.

Detection & monitoring-practical detection rules

Add monitoring rules that will help spot abuse in production:

- Alert: same source (origin / remote page) caused many distinct MCP requests to internal IPs within short window.

- Alert: local API issued requests to cloud metadata endpoints.

- Audit: log the

OriginandX-Local-Authtoken use; periodic review for anomalies. - Telemetry: unusual spikes of outbound local-tool-originated traffic correlate with external browsing sessions.

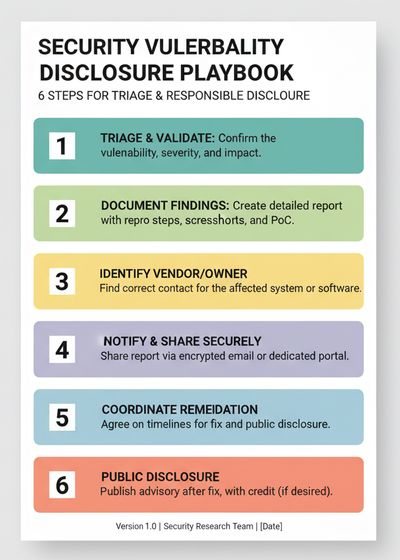

Responsible reporting & triage notes

If you discover a local API issue:

- Stop active probing once you confirm the problem exists.

- Collect minimal, non-sensitive evidence in a controlled lab (screenshots of headers, proof of request acceptance sans sensitive responses).

- Report directly to the vendor’s security contact or bounty program. Include the minimum repro in a lab, risk summary, and suggested mitigations (origin checks, require consent, allowlists).

- Coordinate disclosure; do not publish PoCs until a fix is available.

The researcher who reported the Burp MCP issue followed this path - private disclosure, vendor triage, fix, and bounty - a textbook coordinated disclosure.

Real-world implications & lessons

- Local tools are networked too. Modern apps and dev tools run in complex environments. Treat their local APIs like internet-facing services for security design.

- Default-on convenience is risky. Many problems arise from features that are convenient during development but insecure as shipped.

- Defense-in-depth works. Origin checks + auth tokens + allowlists + explicit consent together dramatically reduce risk.

- User education & telemetry matter. Inform users about the dangers of visiting untrusted pages while having developer tooling enabled, and log suspicious patterns.

Final thoughts

Developer tooling and convenience features are invaluable - but they reshape your threat model. The Burp MCP disclosure is a useful wake-up call: local APIs are not automatically safe. Product teams must assume that local endpoints could be contacted from browsers and design with explicit defenses: origin validation, authentication, user consent, strict capabilities, and safe defaults. Researchers and vendors collaborating responsibly - as happened here - makes these tools safer for everyone.