Lab: Blind SQL injection with conditional errors

Step-by-step, beginner-friendly walkthrough: exploit an error-based blind SQL injection using the TrackingId cookie. Learn how to confirm injection, trigger conditional errors to infer truth, discover password length, extract characters with Burp Intruder, and harden your app.

⚠️ Disclaimer

This write-up is for educational and defensive purposes only. Run these techniques only in legal, authorized environments such as PortSwigger Web Security Academy or your own test systems. Do not use these techniques on systems you do not own or have explicit permission to test.

TL;DR

This lab contains an error-based blind SQL injection - the app performs a SQL query using a TrackingId cookie. The app does not show query results, but it returns a custom error message when a SQL error occurs. By deliberately triggering or preventing an error inside a conditional expression, we can infer boolean facts about the database (existence of tables, password length, character values) and extract the administrator password, then log in.

Key successful payload patterns (sanitized):

This guide explains each step in plain language, shows exact Intruder setup, covers optimizations (binary search / ASCII), gives troubleshooting tips, and details defensive actions for developers and ops.

1 - What the lab teaches (plain language)

Error-based blind SQLi uses SQL errors as an oracle. We craft an expression that will raise an error only if some condition is true. The application will return a recognizable error response (or HTTP 500) when the error occurs, and behave normally otherwise. By observing which requests cause an error, we can learn secrets one bit/character at a time - even when the app does not show query output.

In this lab the injection point is a cookie (TrackingId). Cookies are often overlooked but are fully controllable by the client and can reach SQL layers if the server uses them directly in queries.

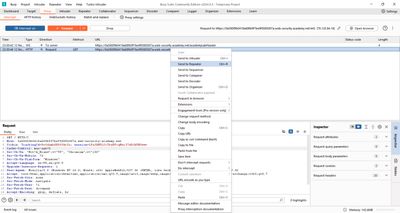

2 - Initial reconnaissance: capture the front-page request

I proxied my browser through Burp and loaded the lab homepage. The front-page GET includes the cookies we care about:

Important: use <TRACKING_TOKEN> and <LAB_HOST> placeholders in writeups. Never publish real tokens.

First sanity check: does injecting a stray quote cause a detectable error?

-

Send:

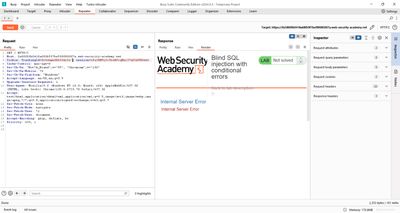

Result: application returned a custom error (internal server error / error page).

-

Send:

Result: error disappeared (syntax corrected).

This tells us two things: (1) the cookie value reaches SQL parsing, and (2) syntax matters - we can craft valid or invalid SQL and detect the difference.

3 - Confirming SQL interpretation and DB flavor hints

Error presence alone might be many things; we must confirm it’s a SQL error. PortSwigger’s example uses dual and Oracle-specific functions to check behavior. I tried to inject a small subquery and adjusted it until it stopped throwing syntax errors:

-

Send:

If this still errors, try:

If adding FROM dual removes the syntax error, it’s a strong hint the backend is Oracle (Oracle requires a FROM clause). In other labs you might use MySQL or PostgreSQL alternatives - adapt based on observed behavior.

Once we know the DB accepts subqueries, we can craft a conditional error payload that raises an error only when a desired condition is true.

4 - Crafting conditional error payloads (the core trick)

The general pattern is:

- Wrap a

CASE WHEN <condition> THEN TO_CHAR(1/0) ELSE '' ENDinside a subquery concatenated into the cookie value.TO_CHAR(1/0)forces a divide-by-zero or similar error only when the condition is true. Concatenate so the surrounding SQL remains valid.

Example check for table existence:

This produces an error because 1=1 is true. If you change it to 1=2, the condition is false and no error.

To confirm the users table exists:

But a simpler confirmed variant used in the lab is:

This returns an error if the table exists and the WHERE clause returns a row.

Important: Use DB-specific functions/operators (SUBSTR, LENGTH, ROWNUM, TO_CHAR, TO_NUMBER) depending on the DB you fingerprinted.

5 - Finding password length (bounding the secret)

Before extracting characters, determine how long the admin password is. Use boolean length checks of the form:

Start at N=1 and increment until the condition is false. The point where the error disappears is the true length. In this lab the length is 20.

Practical speed-ups:

- Use a binary search (test >8, >16, etc.) to reduce requests when length is large.

- Keep requests small and clearly logged so you can reproduce steps in a report.

6 - Extracting characters with Burp Intruder

Character-by-character extraction is the heavy-lift. Use Burp Intruder to automate tests for each position:

Intruder setup (step-by-step)

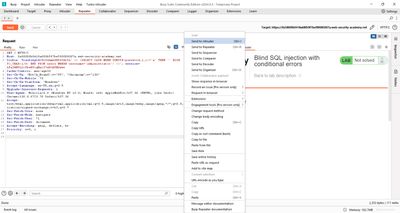

- In Burp, right-click the verified front-page request and Send to Intruder.

- In Intruder → Positions, find the

TrackingIdcookie. Replace the target character in the payload with markers so the cookie looks like:

- Set

§POS§to the position you want (1 for first run). - Set

§CHAR§as the payload slot that will iterate a–z and 0–9.

-

Use Cluster Bomb if you want to test multiple positions and characters in one run; for simplicity I used a single

POSand a singleCHARrun per position (Simple list of characters), repeating the Intruder attack 20 times (one per position). -

In Payloads:

- For the character payload, add

a–zand0–9(lab says lowercase alphanumeric). - If using two positions, set appropriate payload lists (but be careful: permutations explode quickly).

- For the character payload, add

-

In Options → Attack settings:

- Keep concurrency low (to avoid DoS): 5–10 threads max for labs.

- Configure timeouts reasonably.

-

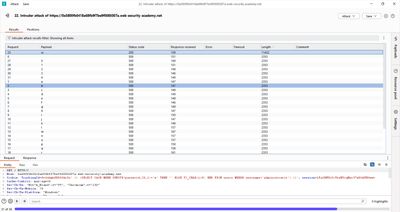

In Intruder → Options → Grep – Match: You can grep for the server error message (or simply watch the Status column). For this lab the server returns HTTP 500 when an error occurs and 200 otherwise, so sort/scan the Status column to find the hit.

-

Start the attack and inspect results. The row with HTTP 500 corresponds to the correct character for that position.

Repeat for positions 1..20, collect characters, and assemble the password.

Notes & optimizations

- Binary-search the ASCII code if the charset is larger. Use

ASCII(SUBSTR(...)) > Xstyle checks. - Throttle and be patient: blind extraction can be slow. Document timings in your report.

7 - Troubleshooting common issues

| Symptom | Cause | Fix |

|---|---|---|

| No error when expected | Payload syntax wrong or not reaching DB | Verify payload in Repeater; ensure proper concatenation and quoting |

| Many 500s in Intruder | Payload markers misplaced or quoting broken | Test a single Repeater request; ensure markers only wrap the character; validate encoding |

| Grep misses error text | Error text is slightly different or encoded | Inspect raw response (Ctrl+U) and adjust grep string or watch HTTP status |

| Attack too slow | Large charset or many positions | Use binary search on length/ASCII; throttle concurrency; test fewer positions first |

| WAF blocks requests | Defense triggered by noisy pattern | Reduce rate, discuss with ops (authorized testing), or use slower manual probing |

Always verify one position manually in Repeater before running a full Intruder attack.

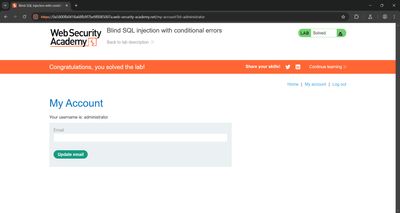

8 - Confirming and using the password

After extracting all characters I tested the admin login:

If the credentials are correct the application authenticates and the lab success banner appears. When reporting, do not publish raw passwords - redact or show a redacted screenshot.

9 - Defensive perspective (how to stop this)

This is the most important section for defenders - make these fixes a priority.

9.1 Code-level fixes (must do)

- Use parameterized queries / prepared statements: never build SQL strings with untrusted input (cookies included). This is the primary and most effective fix.

- Whitelist cookie formats: for a tracking cookie, accept only a safe format (UUID, base64 token) and validate server-side before using it in SQL.

9.2 Reduce error visibility

- Don't return detailed DB errors to users. Use generic error pages and log details server-side.

- Avoid response content that differs meaningfully based on internal query results. Uniform responses reduce oracle surface.

9.3 Privilege separation & data segregation

- Ensure the DB account used by public pages lacks access to sensitive tables (users, secrets). Principle of least privilege limits impact.

9.4 Monitoring & WAF

- Monitor for cookie values containing quotes, SQL keywords (

SELECT,CASE,TO_CHAR, etc.). - WAF rules should flag patterns used for error-based probes.

- Alert on repeated requests altering the same parameter in short windows.

9.5 Tests & CI

- Add automated security tests that send malformed cookies and assert no DB error or different response is observable in staging.

- Include blind-SQLi checks in your security test suite.

10 - Reporting & ethical handling

When reporting this issue:

- Provide reproducible steps (example requests, Intruder settings), but redact any extracted secrets or include screenshots with redaction.

- Provide remediation steps (parameterize, whitelist, limit DB privileges).

- Coordinate credential rotation if any secrets were discovered during authorized tests.

- Retest after fix and include validation evidence.

11 - Final thoughts & next steps

Error-based blind SQLi is powerful but avoidable. The lab shows how small differences in responses become oracles. Defensive controls are straightforward: parameterize, validate, reduce information leakage, and monitor suspicious input.

References & further reading

- PortSwigger Web Security Academy - Blind SQL injection labs.

- OWASP - SQL Injection Prevention Cheat Sheet.

- Burp Suite docs - Intruder and Repeater usage.

- Articles on boolean- and error-based blind SQLi techniques and optimizations.