Lab: Blind SQL injection with out-of-band data exfiltration

Beginner-friendly, step-by-step walkthrough for PortSwigger's lab: blind SQL injection with out-of-band data exfiltration. Learn how to trigger a Collaborator callback that leaks the administrator password, and - critically - how to prevent and detect this in real systems.

⚠️ Disclaimer

This write-up is strictly for education and defensive research in legal, controlled environments such as PortSwigger Web Security Academy or your own lab systems. Do not use these methods against systems you do not own or have explicit authorization to test. The payloads below use placeholders (<BURP_COLLAB>, <LAB_HOST>); replace them only when working on an authorised lab.

TL;DR

This lab shows how a blind SQL injection can be escalated into a data exfiltration channel by forcing the database (or its XML parser) to make an outbound network request to an attacker-controlled host. The lab requires using Burp Collaborator (the Academy permits only the public Collaborator). The key trick is to inject an XML external entity (XXE) into a function like EXTRACTVALUE(xmltype(...)) so the DB resolves a SYSTEM resource containing the administrator's password as part of the hostname. When the DB tries to resolve that hostname, the Collaborator records it - and the secret appears in the subdomain.

In short: we cause the server to call out, capture that call with Collaborator, read the password embedded in the subdomain, and log in as administrator. The defensive lessons are immediate: parameterize queries, disable external entity resolution, restrict DB egress, and monitor DNS/HTTP calls from DB hosts.

1 - What you are solving (lab objective)

Goal: Use the tracking cookie injection to trigger an out-of-band (OOB) DNS/HTTP interaction with Burp Collaborator such that the administrator password appears in the collaborator interaction. Use that password to log in as the administrator.

This lab is a controlled example of OAST (Out-of-band Application Security Testing) - a technique attackers use where direct responses are impossible or suppressed.

2 - Short conceptual overview (for beginners)

Blind SQL injection = the application does not return query results. That usually blocks straightforward data extraction.

Out-of-band (OOB) = instead of asking the app to return data, we make the server reach out to us. Examples: DNS lookup, HTTP GET, or a callback to a controlled host. Because the server makes the connection, the attacker receives the secret externally.

Why DNS subdomains? DNS labels are easy to inject short strings into, the resolver will request them, and many systems allow DNS queries where other outbound traffic would be blocked. In this lab we use XML entity expansion to cause the DB server to perform the lookup.

3 - Recon: confirm injection surface

- Open the lab in your browser while proxying through Burp.

- Locate the front-page GET in Proxy → HTTP history; it contains the cookie header:

- Send that request to Repeater for experimentation. The

TrackingIdcookie is the injection point.

I always keep placeholders <LAB_HOST> and <TRACKING_TOKEN> in public write-ups. Replace them when running the lab.

4 - Prepare Burp Collaborator

Before injecting, create a Collaborator host:

- In Burp Suite, open Collaborator client.

- Click Insert Collaborator payload - Burp provides a unique host such as

abc123xy.burpcollaborator.net. Copy it. This will be<BURP_COLLAB>in payload examples.

Important: the Academy requires you use the public Collaborator server; in real pentests you may host your own OOB server.

5 - The OOB payload explained (Oracle example)

PortSwigger’s example uses Oracle’s XML functions. I’ll explain the structure and reasoning so you understand why it triggers a callback.

URL-encoded payload (safe to paste into cookie value):

Readable version (for study):

How it works:

xmltype(...)builds an XML document that includes a DOCTYPE defining an external entity%remotethat points tohttp://<password>.<BURP_COLLAB>/.EXTRACTVALUE(...,'/l')forces XML parsing and entity resolution. When resolved, the XML parser attempts to fetch theSYSTEMresource, which translates to a DNS/HTTP request for<password>.<BURP_COLLAB>.- The

(SELECT password FROM users WHERE username='administrator')is evaluated and concatenated into the host label by the database - so the database's resolver looks up a hostname that includes the admin password. - Burp Collaborator receives that lookup and shows the password in the recorded interaction.

Because this runs on the server side, the app's HTTP response may not change - but the Collaborator shows the callback.

6 - Step-by-step (my hands-on process)

I’ll describe a reliable, repeatable sequence I used in the lab. Keep everything minimal and documented.

-

Get a Collaborator host

- In Burp choose Insert Collaborator payload and copy the generated subdomain. I pasted that into the payload in place of

<BURP_COLLAB>.

- In Burp choose Insert Collaborator payload and copy the generated subdomain. I pasted that into the payload in place of

-

Send request to Repeater

- From Proxy HTTP history, right-click the front-page GET → Send to Repeater.

-

Replace cookie value

- In Repeater, replace the

TrackingIdvalue with the URL-encoded EXTRACTVALUE payload shown above. Ensure you use the exact Collaborator host.

- In Repeater, replace the

-

Forward the request

- Click Go in Repeater. You might get the same page response - that’s expected.

-

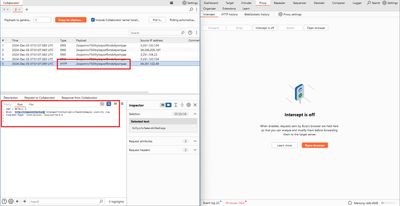

Poll Collaborator

- Switch to the Burp Collaborator tab and click Poll now. Within seconds you should see interactions (DNS/HTTP) from the lab host. Open the interaction details.

-

Read the subdomain

- In the interaction description or Host header you’ll see something like

4r8pi3e5mmezb0kmfngw.<BURP_COLLAB>. Here4r8pi3e5mmezb0kmfngwis the administrator password in the lab example.

- In the interaction description or Host header you’ll see something like

-

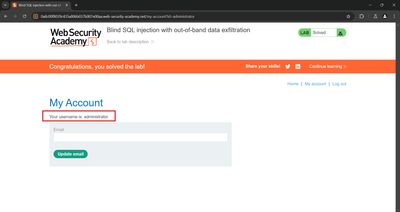

Login

- Use the recovered password to log in at

/loginasadministrator. The lab should mark as solved.

- Use the recovered password to log in at

I took screenshots at the Repeater payload and Collaborator results for my report.

7 - Common gotchas and troubleshooting

If you don’t see a Collaborator interaction:

- Payload truncated: Cookies may be length-limited. Shorten the cookie prefix (e.g., set

TrackingId='...so less initial content exists) so the payload fits. - URL-encoding mistakes: Use Burp's Insert Collaborator helper to avoid encoding errors.

- Wrong DB flavor: Payload shown is Oracle-specific; labs that run other DBs require different OOB tricks. Check earlier labs for DB fingerprinting.

- Collaborator polling delay: The lab executes the query asynchronously; sometimes it takes a few seconds. Click Poll now a couple times.

- Network controls: In real networks outbound DNS/HTTP might be filtered. In the Academy the firewall allows Collaborator; in real tests coordinate with ops or use a permitted channel.

8 - Alternatives & broader OAST techniques (defender awareness)

OOB injection isn't limited to XML/EXTRACTVALUE. Other techniques include:

- DNS exfiltration via concatenated subdomains (as used here). DNS labels can carry short secrets.

- HTTP callbacks via UDFs or HTTP helper functions (if DB or extensions support it).

- SMB/SMTPS/LDAP callbacks - some Windows/MS SQL environments allow triggering remote SMB or LDAP lookups.

- Combining SQLi + XXE - as lab demonstrates, chaining vulnerabilities and server components (SQL + XML parser) often enables OOB.

Defensive teams must assume attackers can chain components. The fix is not "block this payload" but "remove ability to treat user input as code" (parameterize) and "stop the server talking to arbitrary external hosts" (egress control).

9 - Detection & monitoring (practical recipes)

Detecting OOB is possible and practical:

- Egress DNS logging: Log all DNS queries from DB and app servers. Alert on queries with long random-looking prefixes or requests to unknown external domains. Correlate with unusual application activity timestamps.

- Collaborator-like patterns: Monitor for repeated requests to newly observed domains shortly after user-supplied input.

- WAF signatures: Block or alert on XML entity declarations (

<!DOCTYPEandSYSTEM) orEXTRACTVALUE(xmltype(patterns in inputs/cookies. These are high-fidelity triggers for XML-based OOB attempts. - SIEM rule example: IF DNS query originates from DB host AND subdomain length > 20 OR contains base64-like chars THEN alert high.

- Rate-limit and geo-fence egress: If DB servers must speak outward, restrict them to known update servers and log everything.

10 - Fixes and prioritized remediation (what to do now)

If you are the owner of the app or advising a team, apply the following in order:

- Parameterize every SQL query - prepared statements eliminate SQL injection. This is the primary fix.

- Disable external entity resolution (XXE) on any XML parser. Configure parser factories to disallow DOCTYPE declarations and external entities.

- Egress filtering - block database servers from making arbitrary DNS/HTTP requests. Allow only well-audited channels.

- Reduce DB privileges - web-facing DB accounts should not be able to call packages or run OS-level commands.

- Hide DB errors - do not show any DB or parser stack traces to end users. Log them internally.

- Add WAF rules - block or log

EXTRACTVALUE,xmltype,<!DOCTYPE, or patterns that indicate embedded entity declarations. - Add tests - automated security checks that attempt benign OOB payloads in staging and fail builds if any succeed.

11 - Real-world impact & two brief case scenarios

Case A - Credential leak via DNS

A team I audited had a legacy analytics function that interpolated cookie values into a query. An attacker used DNS OOB to recover API keys from a table; those keys allowed pivoting to other services. Fix: parameterize, rotate keys, and block DB egress.

Case B - Supply-chain exposure from verbose XML parsing

An internal integration parsed vendor XML with external entities enabled. Attackers used OOB to exfiltrate internal hostnames and environment variables via DNS. Fix: disable XXE, sanitize vendor inputs, and restrict outbound DNS.

These examples highlight that OOB attacks are stealthy and effective; they must be blocked at multiple layers.

12 - Reporting & responsible disclosure (how to document your findings)

When reporting OOB SQLi:

- Include sanitized request examples (use

<BURP_COLLAB>and<LAB_HOST>placeholders). - Attach Collaborator evidence screenshots (redacted as needed) showing the secret in the interaction.

- Provide a clear remediation plan (parameterize, disable XXE, block egress).

- If you extracted secrets in a real test, recommend credential rotation and a forensics review before public disclosure.

13 - Quick checklist (copy-paste for your PR or bug tracker)

- Replace all dynamic SQL concatenation with parameterized queries.

- Disable external entity resolution in XML parsers.

- Implement egress firewall rules for DB and app servers.

- Rotate any credentials that may have been exposed.

- Add logging and alerts for DNS requests from DB hosts.

- Add automated tests that attempt OOB payloads in staging.

14 - Appendix: safe, lab-only payloads (placeholders)

Only use these in authorised labs and replace <BURP_COLLAB> with the Collaborator host inserted by Burp.

URL-encoded (paste into cookie)

Readable variant (for study)

15 - Final thoughts

This lab is a compact but powerful demonstration: even when an application does not return query output, attackers can often make the server speak for them. OOB channels are stealthy and high-impact. The defensive answer is not hunting payloads, but eliminating the root causes: unparameterized SQL and permissive server configurations (XML entity expansion, open egress). Fixing those will stop this class of exploit and many others.

References

- PortSwigger Web Security Academy - Blind SQL injection / Out-of-band labs.

- OWASP - XML External Entity (XXE) Prevention Cheat Sheet.

- Burp Suite docs - Collaborator client and helper features.