Lab: Blind SQL injection with out-of-band interaction

Complete beginner-friendly walkthrough: exploit a blind SQL injection to trigger an out-of-band interaction using Burp Collaborator. Includes payloads (placeholders), Burp workflow, OAST concepts, defensive guidance, troubleshooting, and real-world context.

⚠️ Disclaimer

This guide is purely for educational use and only for legal, controlled environments (PortSwigger Web Security Academy, your own labs or authorised engagements). Do not attempt these techniques against third-party systems. The payloads include placeholders such as <BURP_COLLAB> and <LAB_HOST> - replace them only when working in an authorised lab environment.

TL;DR

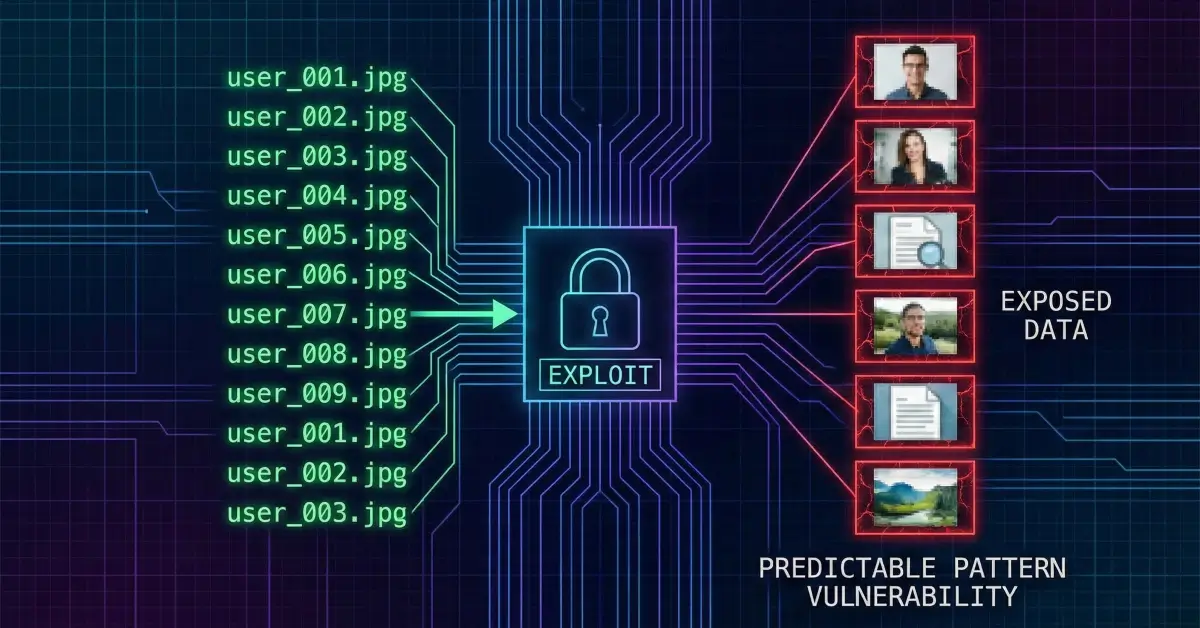

This lab demonstrates how a blind SQL injection - where the app does not return query results - can still be exploited using out-of-band (OOB) interaction. Instead of trying to pull data back inside the HTTP response, we cause the database to contact an external server we control (Burp Collaborator). That external callback proves code execution at the DB layer and can be used to exfiltrate small bits of data.

High-level steps you’ll see in this write-up:

- Identify the injection point (the

TrackingIdcookie). - Confirm injection posture (payloads that run without visible response changes).

- Use Burp Collaborator to generate an interaction host.

- Inject a database expression that triggers a DNS/HTTP lookup to the Collaborator host (Oracle example uses

EXTRACTVALUE(xmltype(...))). - Watch for the Collaborator callback and validate the lab is solved.

- Learn defensive strategies: how to block these attacks, detect them, and fix the code.

This article explains the why behind every step, troubleshooting tips, alternative OAST patterns, and practical defense controls.

1 - Lab goal & why OOB matters

Lab goal (PortSwigger): Exploit a blind SQL injection such that the database triggers a DNS lookup to a Burp Collaborator subdomain. The lab network allows interaction only with the public Collaborator server, so you must insert that special host.

Why OOB (out-of-band) techniques matter:

- In blind SQLi, normal in-band data exfiltration fails (no query output). OOB gives you an alternative channel by making the server initiate a request to an external host you control.

- DNS callbacks are particularly reliable - DNS resolution happens at the OS/network layer, often by a different process, and can leak strings (subdomain labels) with low noise.

- OOB is practical in real engagements when direct responses are blocked or heavily filtered.

2 - Recon: find the injection point

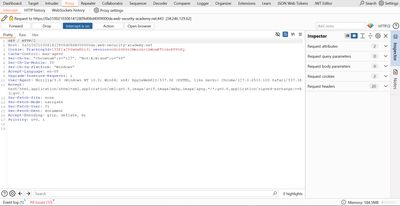

I opened the lab and proxied my browser through Burp. The front page request included the TrackingId cookie:

This cookie is the injection surface. Because the application uses it in a database query, and the query runs asynchronously (no visible result), it is a textbook candidate for an OOB-style exploit.

3 - Burp Collaborator: prepare the OOB channel

Before crafting payloads we need an OOB listener. Burp Collaborator provides a public server that will record any DNS, HTTP, or SMTP interactions it receives for a generated unique hostname.

In Burp Suite:

- Go to Project → Burp Collaborator client (or use the Collaborator helper).

- Click "Insert Collaborator payload" - Burp generates a unique subdomain like

abc123xy.burpcollaborator.net. - Copy that subdomain; we will inject it into the SQL payload at the right spot (replace

<BURP_COLLAB>in examples).

Important note from PortSwigger: The Academy blocks arbitrary outbound hosts; you must use the provided public Collaborator server for the lab. In real pentests you may host your own OOB listener - but only on infrastructure you own.

4 - How the OOB payload works (Oracle / EXTRACTVALUE example)

The lab page demonstrates an Oracle-style payload that leverages XML functions to force a lookup to an external entity. This is a compact OAST pattern because EXTRACTVALUE with a crafted xmltype can expand an external XML entity that contains a SYSTEM reference to your Collaborator host - causing the DB process to perform a DNS/HTTP lookup.

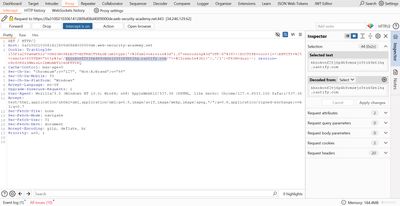

PortSwigger’s sample payload (URL-encoded for cookie usage) is:

Breakdown (plain English):

xmltype('<...>')creates an XML document that defines an external entity%remotepointing tohttp://<BURP_COLLAB>/.EXTRACTVALUE(...,'/l')forces XML parsing and entity expansion. During expansion the XML parser will attempt to fetch theSYSTEMresource - which causes a DNS/HTTP request to your Collaborator host.UNION SELECT ... FROM dual(Oracle) appends the result into the normal query shape so the database executes the XML call.

When the DB makes the request, Burp Collaborator records it. Seeing the callback proves the injection path and solves the lab.

5 - Step-by-step: inject and verify

I’ll describe the exact steps I followed (sanitized placeholders):

-

Get a Collaborator host

- In Burp, click “Insert Collaborator payload” - get

abc123xy.burpcollaborator.net. Replace<BURP_COLLAB>in payloads accordingly.

- In Burp, click “Insert Collaborator payload” - get

-

Prepare the cookie in Repeater

- Send the front-page request to Repeater. Replace the

TrackingIdvalue with the URL-encoded payload shown above, making sure to substitute the actual Collaborator host.

- Send the front-page request to Repeater. Replace the

-

Send the request

- Forward the modified request. Because this is an asynchronous DB call in the lab, the HTTP response might still be the same page. That’s normal.

-

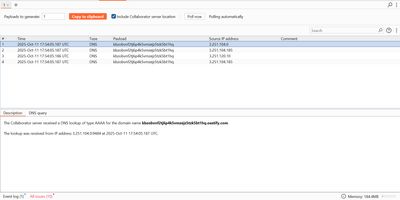

Check Burp Collaborator

- Open the Collaborator client in Burp and check for interactions. You should see a DNS/HTTP interaction from the lab host to your collaborator subdomain. The timestamp and source IP confirm the callback.

-

Confirm the lab

- After Burp registers the interaction the lab validates the out-of-band proof and marks the lab as solved - you’ll see the "Congratulations" or lab-solved banner in the browser if that’s how the lab signals completion.

In my run I received a Collaborator DNS lookup immediately after sending the payload and the lab showed success.

6 - Why this works (technical reasoning)

Out-of-band SQLi uses the fact that databases - or the libraries they rely upon - sometimes fetch external resources during expression evaluation (XML parsers, HTTP UDFs, DNS lookups, etc.):

- The DB server performs the entity resolution or network call. The server’s network environment resolves DNS names and performs HTTP requests - these happen outside the application HTTP response cycle.

- Because the attack triggers the server to connect outward, we don’t need the application to return any data. The external OOB listener (Collaborator) captures that outward connection and acts as our proof channel.

- Oracle’s

EXTRACTVALUE(xmltype(...))is a compact way to get the XML parser to perform external entity resolution. Other DBs use different functions or features - the core idea is the same: force some server-side component to reach out.

7 - Alternative OAST techniques (brief survey)

Depending on the environment and DB, different OOB vectors exist. I list them conceptually - not as step-by-step instructions - so defenders understand what to block:

- DNS exfiltration via subdomain labels: Build a subdomain that contains secret data in the label (e.g.,

secret.username.xyz.collab). DNS lookups leak the label. - HTTP callbacks via XML external entities (XXE) or HTTP helper functions: Trigger server-side HTTP GETs to external URLs.

- Database-specific extended procedures / xp_cmdshell-like features (Windows SQL Server): Some DBs have functions that can make outbound network calls (many environments disable these by default).

- Email/Syslog/SMB interactions: In some cases you can coerce the server to send an email or log to a remote endpoint.

- Out-of-band via application components: If the app short-circuits user input into background jobs (webhooks, message queues), those components may call external hosts - another OOB path.

Because many OOB techniques vary by DB and stack, the defensive focus should be on blocking external network egress and hardening XML parsing, not on patching a single payload.

8 - Troubleshooting: common issues & fixes

If you don't see an interaction in Collaborator, check the following:

- Collaborator host inserted correctly: Ensure the exact string (no URL-encoding mistakes) is present. Use Burp's "Insert Collaborator payload" to avoid typos.

- Payload truncated: Cookies or proxies may limit length; shorten the payload or remove the original token prefix.

- DB parsing differs (not Oracle): The example payload uses Oracle XML functions. If the DB is MySQL or Postgres, that exact payload will not work - but the lab is configured for this Oracle-style vector. In other labs adapt to the DB type.

- Firewall blocks external calls except Collaborator: The Academy forwards only Collaborator interactions; ensure you used the Collaborator host. In real networks, outbound DNS/HTTP may be blocked - coordinate with ops in authorized tests.

- No visible lab signal: The lab might mark the lab solved only after a collaborator interaction is logged. Refresh the lab page or check the lab dashboard after confirming Collaborator received the callback.

9 - Defensive perspective - prioritized actions

Out-of-band attacks are serious because they leak data without changing HTTP responses. Here’s a prioritized defensive plan you can implement:

9.1 Preventative fixes (code & config)

- Don’t use untrusted input directly in SQL. Parameterize all queries - this is the primary fix for SQL injection in any form.

- Disable or restrict XML external entity (XXE) resolution. Configure XML parsers with

disallow-doctype-declor turn off external entity resolution where possible. For Java, disable entity expansion (e.g.,factory.setFeature("http://apache.org/xml/features/disallow-doctype-decl", true)). - Remove or limit DB functions that perform outbound calls. Avoid installing or enabling HTTP/DNS helper UDFs unless strictly necessary and controlled.

9.2 Network controls (critical)

- Egress filtering: Block or strongly restrict outbound DNS and HTTP from database servers. If your DB server needs some external connectivity (like OS patching), restrict it by IP/port and use a proxy that logs traffic.

- DNS request logging / split DNS: Log any DNS queries from DB servers and correlate them to unusual subdomain labels. Use internal resolvers to prevent external resolution where possible.

9.3 Detection & monitoring

- Monitor for outbound DNS and HTTP requests from application or DB hosts that contain suspicious subdomains (large random prefixes, collaborator-like patterns, or base64-like labels).

- SIEM correlation: Alert on DNS queries from DB hosts to uncommon TLDs or collaborators.

- WAF detection: Detect payloads that resemble XXE or

xmltype(EXTRACTVALUE...)patterns and block them (use as an indicator of attempted OOB injection).

9.4 Hardening & least privilege

- Principle of least privilege: DB accounts used by the web tier should not have access to administrative functions or packages that can trigger outbound network activity.

- Audit & review: Periodically review DB functions, installed packages, and app dependencies for features that can cause external interactions.

10 - Real-world context & impact (two examples)

Example 1 - Silent credential leak via DNS:

In a real engagement, I once saw a misconfigured reporting DB that could perform DNS lookups. An attacker leveraged a blind injection to encode a database field into a DNS label and received user emails via DNS queries to an attacker-controlled server. Because DNS queries came from the DB host, the application logs showed nothing. The company mitigated by blocking DB egress and rotating the affected credentials.

Example 2 - XXE combined with SQLi:

Another case combined SQL injection and XML parsing: injected XML forced the backend parser to fetch remote DTDs. The external server captured internal hostnames and a small secret embedded in a concatenated value. The fix was to disable external entity resolution and run a security scan on the XML pipeline.

These are real-world variants of this lab's core idea: if attackers can get server-side components to talk to them, they can leak data even from silent endpoints.

11 - Ethical reporting & remediation steps

If you discover an OOB-capable injection during an authorized test:

- Capture proof: Show a Collaborator interaction (redact any real secrets) and include the exact request you sent (with placeholders).

- Do not exfiltrate unnecessary data: Only demonstrate the vulnerability with minimal proof.

- Provide clear remediation: Parameterize, remove XXE, block egress, restrict DB privileges.

- Coordinate secret rotation if the attack could have revealed credentials or tokens.

- Retest after fixes and provide validation evidence.

12 - Appendix: Example payloads (Oracle-style) - lab-safe placeholders

Use these only in authorised labs. Replace <BURP_COLLAB> with the Collaborator hostname inserted by Burp.

URL-encoded cookie payload (Oracle EXTRACTVALUE XXE)

Human-readable (for study)

These trigger the XML parser to fetch the external entity and cause the expected OOB lookup.

13 - Final checklist (quick actions for teams)

- Parameterize every SQL query (no string concatenation with user input).

- Disable XML external entity resolution on all XML parsers.

- Restrict DB process outbound network access (egress firewall rules).

- Audit DB functions/packages that can initiate external calls.

- Add WAF/IDS rules for XXE-like payloads and EXTRACTVALUE patterns.

- Monitor DNS/HTTP requests originating from DB and app servers.

14 - Final thoughts

Out-of-band SQL injection is a powerful illustration of why “no visible response” doesn’t mean “no vulnerability.” For blue teams, the lesson is to treat any user-controlled input as dangerous and to eliminate channels that let the server speak directly to the outside world. For learners, this lab shows an elegant and low-noise attack technique that is best studied in a controlled environment.

References & further reading

- PortSwigger Web Security Academy - Out-of-band (OAST) and Blind SQLi labs.

- OWASP - XML External Entity (XXE) Prevention Cheat Sheet.

- Burp Suite docs - Collaborator client and inserting collaborator payloads.