Lab: SQL injection vulnerability allowing login bypass

Beginner-friendly, step-by-step walkthrough of PortSwigger's lab: SQL injection that allows login bypass. Includes exact request patterns (placeholders), payloads to practice in labs, real-world examples, defensive guidance and practical detection advice.

⚠️ Disclaimer

This write-up is strictly for educational and defensive purposes and intended for legal, controlled environments (PortSwigger Web Security Academy, local testbeds, or authorized engagements). Do not use these techniques on systems you do not own or have explicit permission to test.

TL;DR

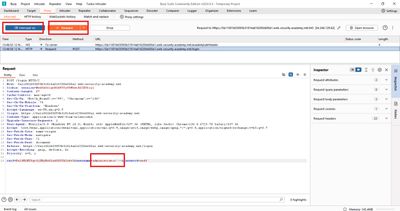

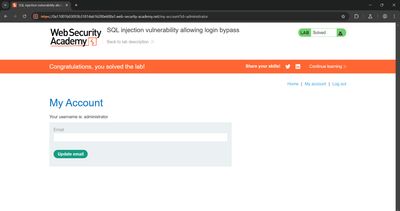

This lab demonstrates a classic SQL injection that lets an attacker bypass authentication. I reproduced the login request in a proxy, replaced only the username value with the lab payload administrator'-- (no space after the --), kept the request format intact, and the application authenticated me as the administrator.

This post documents the full step-by-step process (using <LAB_HOST> and placeholders for sensitive tokens), explains exactly why that payload works, offers troubleshooting and alternate payloads, provides multiple real-world examples where this weakness caused real harm, and delivers developer-focused remediation and detection advice.

For comprehensive SQLi theory and more labs, see our pillar: The Ultimate Guide to SQL Injection (SQLi).

1 - Lab goal & quick notes

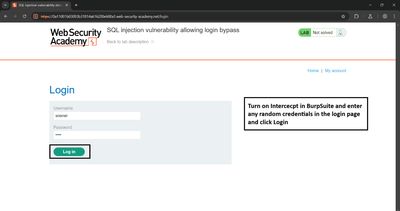

Lab goal (PortSwigger): Exploit the SQL injection vulnerability in the login function to log in as the administrator user.

This is an Apprentice level lab intended to teach the dangers of concatenating user input directly into authentication SQL queries. Despite being simple, the impact is high - bypassing authentication grants immediate access to protected functions and sensitive data.

Before any modification, I captured a normal login attempt to observe the request structure. I preserve the same structure when sending tests so the server accepts the request and the SQL layer is reached.

2 - Capture and inspect the login request (placeholders used)

I proxied my browser through Burp and submitted a normal login (for example: username=wiener, password=asdf). The sanitized request I observed looked like this:

Key observations:

- The request is a standard form POST with

application/x-www-form-urlencoded. - The body contains

usernameandpasswordfields - the likely SQL inputs. - A

csrfparameter was present in this lab; when testing, keep required request fields intact so the request is processed (we use placeholders in published examples).

I used this captured request as the basis for my tests. I only modified the username field to test whether the backend treated input as SQL code rather than data.

3 - The payload I used (exact)

I changed the username value to the payload and left everything else the same (placeholders shown):

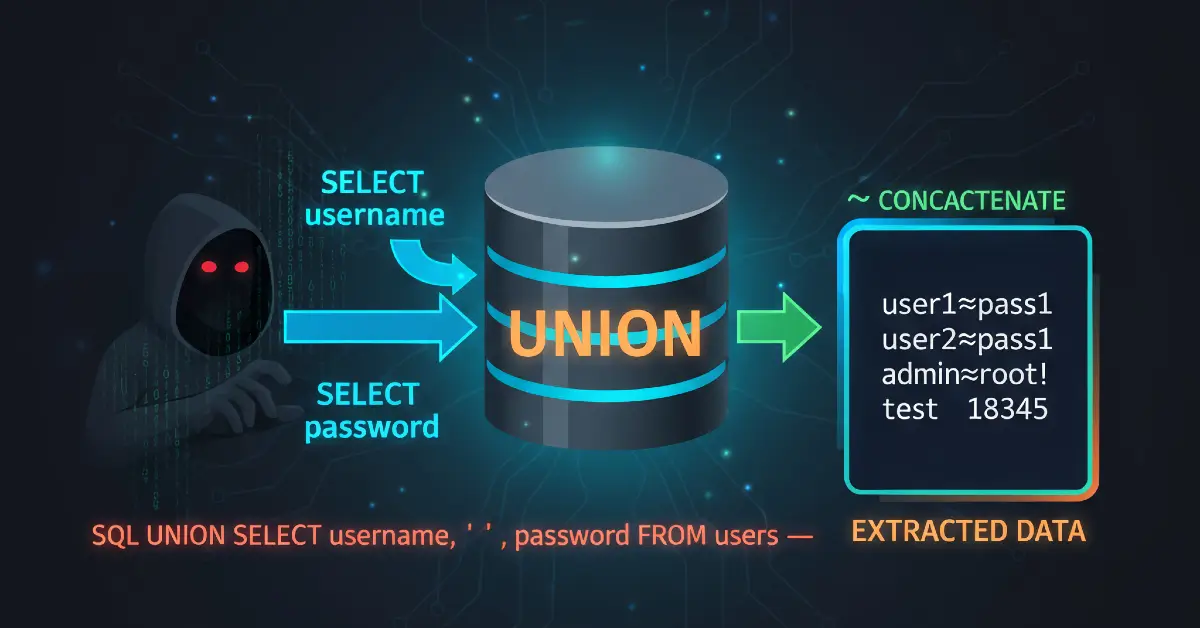

4 - Why this payload works (technical explanation)

A common vulnerable authentication SQL statement looks like:

If the application builds this query by concatenating user values (instead of parameter binding), substituting <USER_INPUT> with administrator'-- leads to:

What happened:

- The

--begins a SQL single-line comment, so the remainder of the line (including theAND password = ...) is ignored by the DB parser. - The WHERE clause simplifies to

username = 'administrator'because everything after--is commented out. - The query returns the administrator row (if it exists) and the application believes authentication succeeded.

Notes for beginners:

- This kind of injection only works when the application trusts the DB result to indicate authentication and does not perform additional server-side validation.

5 - The attacker’s thought process (reconstructed)

Understanding the attacker’s mindset helps both testers and defenders:

- Map inputs - Intercept login requests to see which fields reach the server.

- Hypothesize - If values are concatenated into SQL, injection into username or password can change query logic.

- Test minimally - Preserve the overall request (CSRF token, cookies, headers) and change only the suspected parameter.

- Use the smallest effective payload -

administrator'--directly targets authentication without extra noise. - Confirm action - If login appears successful, validate by accessing admin-only pages or seeing the application’s “logged-in as” UI.

This lab is an excellent demonstration of how a tiny payload in a critical place (login) creates disproportionate impact.

6 - Alternate payloads and troubleshooting

If the simple payload fails, try these troubleshooting steps and alternatives:

6.1 Common reasons for failure

- Quotes are filtered or escaped - try double quotes or encoding.

- Comment syntax differs - some DBMSs require a trailing space after

--. - Prepared statements are used - injection will not work; move to other inputs.

- Token/session issues - ensure you preserved required tokens and cookies in the request.

- The app validates passwords differently - injection may have to target the password field instead.

6.2 Useful variants to try (lab/testing only)

6.3 Encoding and edge techniques

- URL-encode values when sending in a browser context:

%27for',%20for spaces. - Try block comments where supported (

/* payload */), or use database-specific functions if quotes are filtered (e.g., usingCHAR()to construct characters).

Practical tip: Run tests in a controlled lab. If you must test production (only with authorization), be conservative and coordinate with ops.

7 - Confirming authentication bypass (validation steps)

After sending the injected request, confirm you actually have admin access:

- Attempt to access an admin-only URL or dashboard page.

- Check for presence of user info indicating administrator role (e.g., “Logged in as administrator”).

- Observe server responses (redirects to admin area or presence of admin-only elements).

If the lab or app visually indicates success (banner, username), capture that screenshot for notes (do not publish sensitive images). In a real assessment, document the exact path to confirm exploitation.

8 - Real-world examples (why this matters)

Including real-world examples helps readers see practical implications. Below are three concise, real-world scenarios where an auth-bypass SQLi had major consequences.

Example 1 - Login bypass in an enterprise portal

A mid-sized company had an internal HR portal where authentication was implemented via string-concatenated queries. An attacker found that a simple OR style payload led to administrator access. Once inside, they exported employee records including PII and payroll data. The root cause: legacy code that constructed SQL directly from form inputs and an over-privileged DB account.

Key lesson: Even internal apps with few users are high-value targets - fix authentication code regardless of exposure.

Example 2 - E-commerce admin takeover and price manipulation

An online storefront’s admin login had a SQLi vulnerability. Attackers bypassed authentication and accessed product management pages, changing prices and creating discount coupons. Financial loss followed alongside reputational damage. Attackers also discovered staging data leaks through exposed admin functions.

Key lesson: Compromising an admin account can enable immediate business-impacting actions - protect admin auth paths especially tightly.

Example 3 - Chained breach: SQLi → credential theft → cloud compromise

A public-facing web app leaked a database row containing a hashed admin API key after a successful SQLi. Attackers used that key to access internal APIs and, eventually, cloud resources. The SQLi served as the initial foothold in a multi-stage breach. Excessive DB privileges and weak key management amplified damage.

Key lesson: Treat leaked DB values as potentially exploitable credentials - apply least privilege and rotate secrets fast.

These examples show: a simple lab payload maps directly to real-world business risk. That’s why focusing on auth endpoints is critical.

9 - Developer remediation checklist (practical actions)

If you are responsible for the codebase, apply these fixes immediately in the following order:

9.1 Use parameterized queries (primary fix)

Replace any concatenated SQL with prepared statements. Example (PHP PDO):

Prepared statements ensure the DB treats input as data, not code.

9.2 Proper password storage & comparison

- Use slow, salted password hashes (bcrypt, Argon2).

- Compare hashes on the server; never rely on SQL to compare plaintext inputs.

9.3 Input validation & whitelisting (defense-in-depth)

- Validate username formats (email patterns, allowed characters).

- Reject excessively long or control-character-laden inputs at the application boundary.

9.4 Rate limiting & lockout policies

- Apply sensible throttling and progressive lockouts to reduce brute-force effectiveness and make exploitation noisier.

9.5 Least privilege for DB accounts

- The application DB user should have minimal rights - typically SELECT on specific schemas/tables only.

- Avoid granting schema or system-level privileges to web-facing accounts.

9.6 Logging, monitoring & alerts

- Log anomalous login inputs (e.g., containing

'or--) and alert on patterns that match injection attempts. - Monitor for sudden admin logins from new IPs.

9.7 Automated tests in CI

- Add security tests that simulate SQLi attempts against staging. Fail builds when endpoints are injectable.

10 - Detection recipes (WAF / SIEM / DevOps)

Quick detection rules defenders can implement:

- WAF rule: Block or alert on POST bodies to

/logincontaining--,%27,UNION, orSELECTpatterns. - SIEM correlation: Trigger if a single IP has multiple login attempts with SQL-like payloads followed by a success.

- DB audit: Alert on queries where bound parameters are absent and user input appears in logs.

- Anomaly detection: Flag admin logins from unusual geographies or new user agents.

These are stop-gap and detection-focused - they do not replace code fixes.

11 - Practice suggestions and next steps

To strengthen your skills and team readiness:

- Re-run this PortSwigger lab and practice the payloads listed above. Then fix a local intentionally-vulnerable sample app and verify the fix.

- Practice blind and error-based techniques on follow-up labs where direct feedback is limited.

- Run a code audit for dynamic SQL patterns in your codebase and prioritize fixes on auth and admin flows.

12 - Summary & final thoughts

This lab shows how a minimal injection in the authentication path can grant full administrative access. The fix is well-known and manageable: parameterized queries, secure hashing, whitelisting, least privilege, and monitoring. As both hunters and defenders, focus efforts on authentication code paths first - they are high-impact and often under-tested.

References & further reading

- PortSwigger Web Security Academy - SQL Injection labs.

- OWASP Authentication Cheat Sheet - recommended practices for secure login flows.

- OWASP SQL Injection Prevention Cheat Sheet - parameterization and input handling guidance.