Lab: Visible error-based SQL injection

Beginner-friendly, step-by-step walkthrough: leak sensitive data using a visible error-based SQL injection via the TrackingId cookie. Includes exact payloads (placeholders), Repeater/Intruder setup, troubleshooting, detection recipes, and developer remediation steps.

⚠️ Disclaimer

This write-up is for educational and defensive use only. Use these techniques only in legal, controlled environments such as PortSwigger Web Security Academy or your own testbeds. Never run these tests against systems you do not own or have explicit permission to test.

TL;DR

This lab uses an error-based SQL injection in a tracking cookie to force the database to throw an error that contains sensitive data. The site shows a verbose database error when our injected SQL returns non-integer text during an explicit integer cast - so we can leak usernames and passwords directly from the database error message.

High-level steps I followed (sanitized):

- Intercept the front-page request and locate the

TrackingIdcookie. - Append a single quote and observe a verbose DB error (confirm injection point).

- Use comment-out

--to make the query syntactically valid. - Inject a

CAST((SELECT ... ) AS int)payload to force the DB to try to convert text to integer - when it fails, the error reveals the string returned by the subquery. - Limit subqueries to a single row (

LIMIT 1) to avoid multi-row errors. - Extract administrator password and log in.

Key example payloads (replace placeholders with your lab values):

This post explains every step, why it works, troubleshooting, detection and prevention, and real-world implications. Also see our pillar guide: The Ultimate Guide to SQL Injection (SQLi) for deep background.

1 - Lab objective & mental model

Objective: Use the TrackingId cookie injection to leak the administrator password via visible database error messages and then log in as administrator.

Why this is powerful: many apps hide query outputs but still show errors. Errors can contain the actual string that caused the failure. If you can cause a conversion error intentionally (for example, casting a text to an integer), the DB error will often include the offending text - which becomes your leak vector.

The defensive takeaway is simple: never show raw DB errors to end users and avoid building SQL from untrusted input.

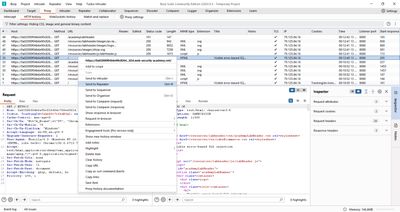

2 - Recon & first checks (find the injection point)

I opened the lab with Burp Proxy turned on and looked in Proxy → HTTP history for a front-page request that included cookies. The relevant piece looked like this (sanitized):

The TrackingId cookie is under my control. That means it might be interpolated directly into a SQL query on the server (common for naive analytics implementations). My first goal was to confirm that the cookie value reaches SQL parsing.

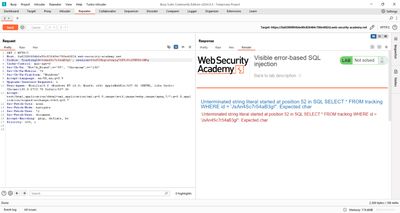

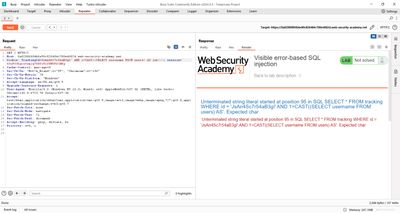

Sanity check - single quote

In Burp Repeater I modified the cookie to append a single quote:

Response: the application returned a verbose error message that displayed part of the SQL query and highlighted an unterminated string literal. This proves:

- Our input is included inside a single-quoted SQL string.

- Errors are verbose and leak internals - a dangerous combination.

If the single-quote had no effect, stop and reassess - maybe the cookie is validated or encoded.

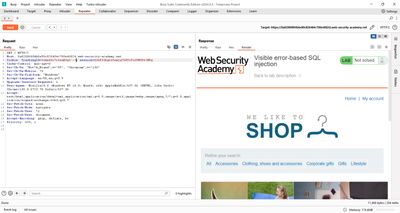

3 - Fixing syntax with comments and testing casting

When I added a trailing comment marker, the syntax error disappeared. That shows the original query after our injection contained trailing characters that cause the unclosed quote. Adding -- comments out the remainder and makes the SQL syntactically valid:

Response: no error (query syntactically fixed).

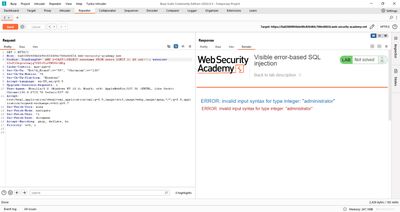

With a clean injection point, I tested the idea of forcing the DB to cast a subquery result to int. The trick: if the subquery returns a string like "administrator" and we try to CAST(... AS int), the DB will error and the error string will include the bad text in many engines (Postgres shows invalid input syntax for type integer: "administrator").

First test:

Response: an error like “argument of AND must be type boolean, not integer” - that tells us that the DB parsed the expression and that we must compare the cast value to something boolean. Adjusting:

Response: no error (valid boolean expression). Good - we can now place a subquery that returns text and wrap it with CAST(... AS int) to cause an error that leaks the text.

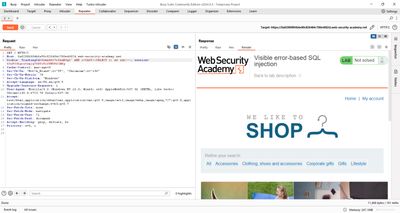

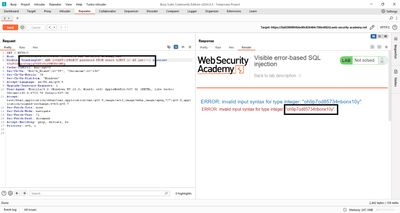

4 - Leaking data: test with username and LIMIT

I replaced the subquery to return usernames:

Result: I got a truncated query error at the server. That indicated two practical problems:

- The application truncated our payload (character limit), which meant we needed to shorten the entire cookie value to fit.

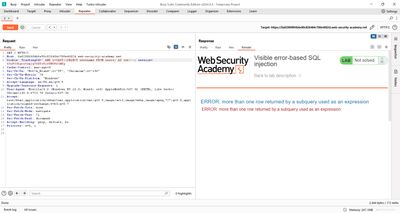

- The subquery returned more than one row, which causes a different error.

To fix both, I removed the original cookie prefix (freeing characters) and added LIMIT 1 to ensure a single row:

Response: the database returned an error like:

ERROR: invalid input syntax for type integer: "administrator"

Perfect - the DB error directly displayed the username of the first row: administrator. That confirms the table contents and order.

Next, I swapped username for password to leak the admin's password:

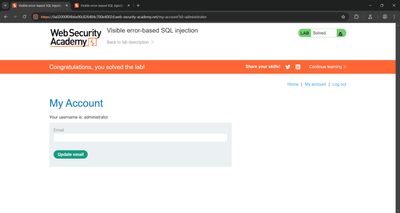

Response: an error with the password string (the lab's password). With those credentials I logged into the site and solved the lab.

5 - Why CAST works (technical explanation)

Many DB systems will attempt to convert types when asked. If we request CAST('some-text' AS int) the DB will raise an error because 'some-text' is not a valid integer. When verbose error reporting is enabled, the DB will include the offending string in the error message:

- Postgres:

invalid input syntax for type integer: "some-text" - Other DBs: similar conversion errors or stack traces

By wrapping a SELECT <column> FROM <table> LIMIT 1 inside that CAST(...) we can cause an error that contains the selected column's value. Because the application displays raw DB errors, this becomes a data-leak channel.

This is why error-based SQLi is powerful and why error messages should be suppressed in production.

6 - Practical tricks and edge-cases I handled

- Payload length / truncation: Some apps limit cookie length. I removed the original cookie value before injection (

TrackingId=' ...) to free space. If the server still truncates, try shorter payloads or use known short column names and avoid verbose casting expressions. - Multiple-row subquery: If your subquery returns many rows you’ll get “more than one row” errors. Always use

LIMIT 1(or an aggregate) when you expect a single value. - Comment markers not included due to truncation: If your appended

--disappears, shorten the whole cookie and re-add it; or use/*...*/if supported and allowed. - DB flavor differences: The example here used patterns common to Postgres. Other DBs (Oracle, MSSQL, MySQL) have different casts and error text - adapt accordingly.

7 - Repeater & data capture (exact workflow I used)

-

Find the GET

/request in Proxy → HTTP history that containsTrackingId. -

Right-click → Send to Repeater.

-

In Repeater, test the following safely (replace placeholders):

Check injection

Fix with comment

Test boolean CAST

Leak username (shortened)

Leak password

-

When the Repeater response shows the leaked value inside the error (for example

invalid input syntax for type integer: "administrator"), copy redacted evidence for your report and use the credentials to log in.

8 - Troubleshooting checklist

| Symptom | Likely cause | Fix |

|---|---|---|

No error after adding ' |

Input sanitized / encoded or cookie not used in SQL | Confirm the cookie is actually used; try other headers or parameters |

Error still occurs after adding -- |

Comment truncated or removed by the app | Reduce cookie value length; remove original token prefix; try /*...*/ if supported |

| "more than one row returned" | Subquery returned multiple rows | Add LIMIT 1 or aggregate (e.g., MAX(username)) |

| Payload too long / truncated | App or proxy enforces limit | Shorten payload, remove original cookie, or use a different injection spot |

| No visible DB error | Errors are suppressed | Switch to blind techniques (time-based or boolean) or check logs if authorized |

9 - Defensive perspective (how developers should fix this)

This is the critical section for the site owners and developers - act on these items first.

9.1 Remove verbose DB errors from user responses

- Never expose raw database error messages to end users. Show a generic error page and log details server-side for developers.

9.2 Use parameterized queries / prepared statements

- The root cause is dynamic SQL interpolation. Switch to prepared statements so inputs are treated as data, not code.

9.3 Validate and canonicalize cookie values

- Accept only a safe format for analytics cookies (UUID, signed token). Reject or validate unexpected characters (quotes, SQL keywords).

9.4 Principle of least privilege

- The DB account used for public pages should not have access to sensitive tables (

users). Use separate roles for public read-only pages.

9.5 Rate limiting & WAF

- Implement rate limits on endpoints and WAF rules to detect and block patterns like

CAST(... AS int)or repeated'injections in cookies.

9.6 CI & security tests

- Add automated tests that send safe SQLi probes to staging endpoints and fail the build if vulnerabilities are detected.

Implementing these steps will remove the immediate attack surface and make error-based leaks impossible.

10 - Detection & SIEM rules (practical recipes)

- WAF rule example (conceptual): block or log request parameters/cookies containing

CAST(+AS intorSELECTinside a cookie/header. - SIEM correlation: alert when the same IP produces multiple requests with

'in cookie values and receives different server errors (500 vs 200). - App logging: store full request and server-side stack traces in an access-restricted log (not shown to users) and alert on errors that include user-controlled input.

- Response fingerprinting: detect when the app returns DB engine-specific error strings (e.g.,

invalid input syntax for type integer) and treat them as high severity.

These detection layers complement code fixes and provide incident visibility.

11 - Real-world examples & impact

Example A - Analytics cookie leak leads to admin takeover

A public portal used the same DB role for analytics and admin tables. An attacker used error-based SQLi in a tracking cookie to reveal admin credentials, logged in, and altered site data. Fix: split DB roles and parameterize queries.

Example B - Supply-chain risk from verbose errors

A vendor's staging server printed DB errors with hostnames and version details. Attackers used this to fingerprint the DB and craft targeted payloads. Fix: remove errors from responses and sanitize logs.

These show how small mistakes cascade into full compromises.

12 - Ethical disclosure & reporting

If you discover this vulnerability:

- Do not publish leaked credentials or secrets. Redact them.

- Provide a minimal PoC (screenshot with redaction) and exact reproduction steps.

- Suggest immediate mitigations (parameterize, hide errors, rotate exposed credentials).

- Coordinate with ops for credential rotation and retest after fixes.

13 - Final checklist for your PR (copy-paste)

- Replace any dynamic SQL that uses cookies with parameterized queries.

- Add server-side validation: accept only expected cookie formats (UUID, signed token).

- Remove or hide raw DB error messages from user responses.

- Limit DB account privileges for the web front-end.

- Add a unit/security test that probes cookie-based SQLi on staging.

- Add WAF signature to detect suspicious cookie patterns.

14 - Final thoughts

This lab clearly shows a common pattern: verbose errors + unparameterized SQL + user-controlled inputs = easy data leaks. The fix is straightforward: parameterize, validate, reduce privileges, and never show raw errors to users. From a learning point of view, practicing this lab trains you to think like an attacker and, more importantly, like a secure developer.

References

- PortSwigger Web Security Academy - Visible error-based SQL injection lab.

- OWASP - SQL Injection Prevention Cheat Sheet.

- PostgreSQL error message documentation (example for

invalid input syntax for type integer).