The Ultimate Guide to SQL Injection (SQLi): Types & Prevention

Comprehensive guide to SQL Injection (SQLi): types, impact, detection, and practical prevention advice for developers and testers.

⚠️ Disclaimer

This guide is for educational and defensive purposes only. Use it in legal, controlled environments such as lab platforms (PortSwigger Web Security Academy) or your own test systems. Do not attempt attacks on systems you do not own or have explicit permission to test.

TL;DR (Quick summary)

SQL Injection (SQLi) allows attackers to manipulate database queries by injecting input that changes SQL logic. This guide explains the major SQLi types (In-band: UNION & error, Blind: Boolean & time), detection methods, hands-on attack patterns to practice in labs, and robust prevention steps you can implement today. Read our Cluster lab write-ups after this guide for practical, step-by-step exercises.

1 - What is SQL Injection? (simple explanation)

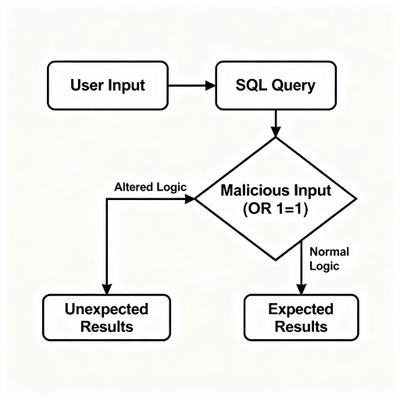

At heart, SQL Injection happens when user input is combined with SQL commands in a way that lets the input be interpreted as code instead of data. When that occurs, an attacker controls the SQL the database executes.

Vulnerable pattern example (pseudocode):

If user_input is Corporate gifts' OR 1=1--, the resulting SQL becomes:

OR 1=1 makes the condition always true and exposes all rows.

Simple takeaway: Never allow user input to become SQL code. Treat inputs strictly as data.

2 - Why SQLi still matters (impact & scale)

Databases are critical: they store PII, financial data, login credentials, business logic tables and more. SQLi can lead to:

- Data exfiltration: full database dumps or targeted rows.

- Authentication bypass: attacker logs in as other users.

- Data manipulation: INSERT/UPDATE/DELETE operations if DB user privileges allow.

- Remote code execution / pivoting: using DB functions to call external services or OS commands (in some engines).

- Wider breach: stolen credentials used to pivot to other systems.

Historic breaches often included SQLi as a primary vector - even a simple OR 1=1 can escalate into major incidents when combined with misconfigurations and excess privileges.

3 - Types of SQL Injection (deep dive)

3.1 In-band SQLi (attacker uses same channel for attack & response)

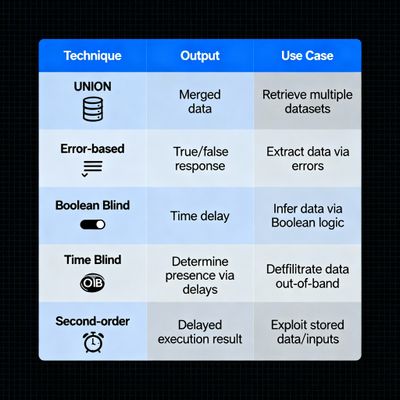

UNION-based SQLi

- Attacker appends

UNION SELECTto merge arbitrary rows with the original query result. Works when the app renders query output. - Process: find column count → find text-capable column →

UNION SELECTarbitrary values.

Error-based SQLi

- Forces meaningful errors that reveal data (e.g., by provoking type conversion errors that include values in error text).

- Less common in hardened production but effective in verbose dev/staging setups.

3.2 Blind SQLi (when results aren’t directly returned)

In blind SQLi the attacker cannot see query results directly. Instead, they infer results via side-channels.

Boolean-based blind

- The attacker sends payloads that evaluate to true or false and observes page differences to infer data. Example:

- By iterating over characters, they reconstruct data (slow but stealthy).

Time-based blind

- Use DB sleep/delay functions to cause measurable delays when a condition is true:

- Infer characters by timing responses. Useful when no output or errors appear.

Out-of-band (OOB)

- Uses network callbacks (DNS/HTTP) for exfiltration when direct or blind channels are blocked (requires DB to make outbound requests).

3.3 Second-order SQLi (stored/indirect injection)

What it is

Second-order SQL Injection (often called stored or indirect SQLi) occurs when attacker input is stored by the application without immediate harmful effect, but later that stored data is used in a different context where it is interpreted as SQL. The initial input might look safe in the first request, so it bypasses quick checks, but when the application later concatenates or reuses that stored value in a query, the malicious payload executes.

Example workflow (conceptual)

- Attacker submits a profile field or configuration value containing a payload, e.g.,

O'Reilly'); DROP TABLE notes;--. - The app stores this value in the database (safe at the time because it isn't executed).

- Later, an admin tool or background job builds a dynamic SQL statement using that stored value without parameterization, causing the stored payload to run.

Simple stored example (illustrative only; practice in labs)

Why it’s dangerous

- It can bypass initial validation and input filters because payloads may be benign-looking during storage.

- The harmful effect appears later in a different code path, often executed by higher-privilege users or backend processes.

- Logging, admin pages, report generation, or scheduled jobs are common danger points.

Detection tips

- Review all code paths that read stored user data and insert it into SQL statements.

- Model threat scenarios where stored content flows into different query contexts (admin queries, batch jobs, reporting).

- In pentests, try submitting payloads to storage endpoints and then trigger any functionality that later reads those values (view-as-admin, export features, scheduled reports).

Prevention

- Treat stored data as untrusted whenever it’s later used in SQL: always use parameterized queries at all points of use.

- Avoid building dynamic SQL with stored values. If dynamic SQL is unavoidable, use strong whitelists and safe APIs (prepared statements, stored procedures with parameters).

- Escape and canonicalize when showing stored data in other contexts, and apply least privilege for processes that consume stored inputs.

When to include this in testing

Always include second-order test cases in your test plan, especially for features that persist user data (profiles, settings, comments, uploads) and for admin/reporting functionality that re-uses stored data in SQL queries.

4 - How attackers think: practical techniques to practice

I recommend practicing all of these in a lab (PortSwigger, DVWA, Juice Shop) - never on production.

Quick confirmation (boolean)

If result set widens, injection likely exists.

UNION extraction (when app shows results)

- Determine column count:

- Identify text column:

- Extract:

Error-based pattern

- Force an error that includes data, e.g. conversion errors or deliberate division-by-zero-like constructs that leak info.

Blind enumeration (boolean/time)

- Iterate characters with

SUBSTRINGor useSLEEP()to infer values.

5 - Detection & testing checklist (for pentesters)

When testing or scanning, follow this checklist:

- Map input surface: All query params, POST bodies, headers, cookies.

- Quick boolean tests:

' OR 1=1--,' AND 1=0--. - Error probes: Submit malformed inputs to trigger DB errors (only in labs or with permission).

- UNION column counting: Incremental

NULLs to find column number. - Automated scan:

sqlmap(in labs) to find variants. - Manual verification: Confirm

sqlmapfindings manually to avoid false positives. - Blind tests: If no output, try boolean/time-based payloads.

- Record exploitability: Depth of extraction, potential privilege escalation, and OOB options.

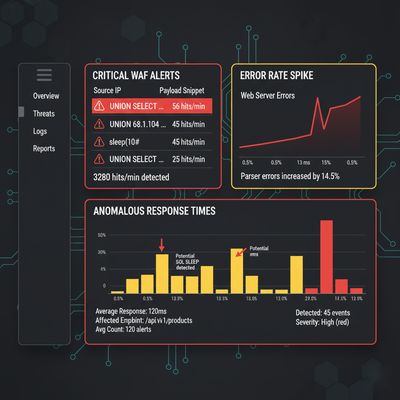

6 - WAF and SIEM signals (what defenders should monitor)

Practical, actionable alerts you can implement:

-

WAF rules: block/alert on repeated requests having quotes,

UNION,SELECT, orSLEEP(patterns from a single IP or session. -

SIEM correlation:

- Sudden spikes in queries containing quotes,

UNION,SELECT, orSLEEP. - Requests triggering DB error logs with stack traces.

- Outbound DNS/HTTP requests originating from DB server (possible OOB exfil).

- Sudden spikes in queries containing quotes,

-

RUM & response timing: clusters of requests with increasing latency that match

SLEEP()trials. -

Anomaly detection: access to metadata tables like

information_schemaby web app account.

Add these as detection recipes in your alerting runbook.

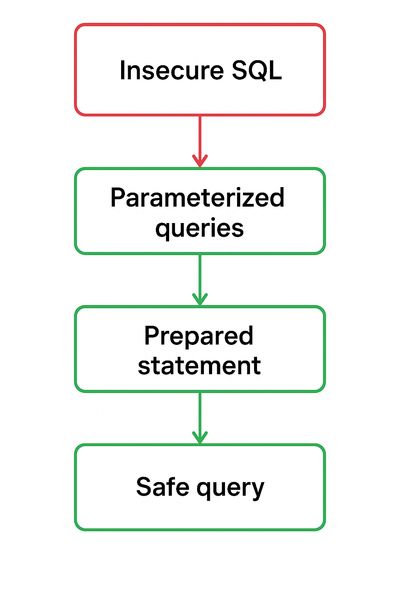

7 - Fixes & developer checklist (practical, apply today)

-

Parameterized queries / Prepared statements (non-negotiable)

- Never build SQL by concatenating user input. Example:

- PHP PDO:

- Node/pg:

-

Whitelist & canonicalization

- For categories, use enums or look up allowed values and reject all others.

-

Least privilege & role separation

- App DB user should have minimum rights (typically SELECT/INSERT on app tables only).

-

Disable risky DB features

- If you don’t need file reads, outbound HTTP, or command execution, disable or restrict them.

-

Sanitize & encode output

- Prevent XSS when rendering DB content.

-

CI security tests

- Add automated SQLi testcases against staging endpoints for regression.

-

Error handling & logging

- Avoid exposing DB errors to users. Log internally with context for triage.

-

WAF as a layer

- Deploy WAF for general protection and to buy time while fixing code.

8 - How to remediate at scale (security team playbook)

If you discover SQLi in production:

- Immediate: rotate credentials where feasible, restrict DB egress, put critical endpoints behind WAF rules.

- Short-term: patch endpoints with prepared statements, add whitelists.

- Long-term: audit codebase for dynamic SQL, enforce secure coding standards, and run regular pentests.

Document steps in an incident runbook: triage → contain → fix → retest → audit.

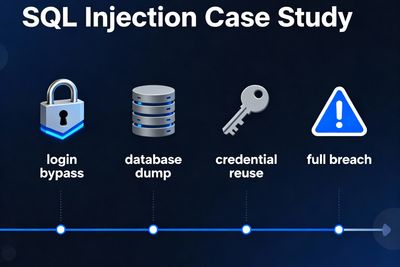

9 - Extended real-world case studies

Case study A - Login bypasses (classic)

A poorly coded login used:

An attacker used admin' -- as username and bypassed password checks. Lesson: avoid string concatenation and never trust user-supplied credentials.

Case study B - E-commerce product leaks

An e-commerce site’s filter revealed hidden SKUs. Attackers changed category param to include OR 1=1 and enumerated internal stock not yet published, finding staging SKUs and discount codes. Damage: leaked business plans and price manipulation.

Case study C - High-impact breach chain

SQLi exploited in a company with a DB user having excessive privileges allowed data exfiltration and discovery of credentials. Those creds were reused to access admin panels and cloud resources, resulting in a major breach. The root cause: insecure queries + over-privileged accounts.

Lessons: Prevention is not just code-level - it’s permissions, egress controls, and monitoring.

10 - FAQ (short, practical answers)

Q: Is SQLi only a SQL Server problem?

A: No - MySQL, PostgreSQL, SQL Server, Oracle all can be vulnerable if queries are built insecurely.

Q: Can WAF replace secure coding?

A: No. WAF is a protective layer, not a substitute for prepared statements and input validation.

Q: How fast can blind SQLi extract a password?

A: Very slowly - blind extraction is time-consuming; use it only when direct extraction is blocked.

Q: What are safe tools for testing?

A: Burp Suite Community (intercept + Repeater), Turbo Intruder for raw TCP ordering (labs), and sqlmap for automation - only on authorized targets.

11 - Where to practice (Cluster Posts & Labs)

Practical labs cement theory. Start with:

- Lab: SQL injection vulnerability in WHERE clause allowing retrieval of hidden data - beginner, UNION intro.

- Lab: SQL injection vulnerability allowing login bypass

- Lab: SQL injection UNION attack - determining number of columns returned by the query

- Lab: SQL injection UNION attack - finding a column containing text

- Lab: SQL injection UNION attack - retrieving data from other tables

- Lab: SQL injection UNION attack - retrieving multiple values in a single column

- Lab: SQL injection attack - querying the database type and version on MySQL and Microsoft

- Lab: SQL injection attack - listing the database contents on non-Oracle databases

- Lab: Blind SQL injection with conditional responses

- Lab: Blind SQL injection with conditional errors

- Lab: Visible error-based SQL injection

- Lab: Blind SQL injection with time delays and information retrieval

- Lab: Blind SQL injection with out-of-band interaction

- Lab: Blind SQL injection with out-of-band data exfiltration

- Lab: SQL injection with filter bypass via XML encoding

- Lab: SQL injection attack, querying the database type and version on Oracle

- Lab: SQL injection attack, listing the database contents on Oracle

- Lab: Blind SQL injection with time delays

Work labs in this order: confirm → enumerate → extract → remediate.

12 - Tools & cheat-sheet (copy-paste friendly)

Quick boolean check:

Column count probe (UNION):

Find text sink:

13 - Final thoughts

SQL Injection is simple to learn but expensive to ignore. A few disciplined engineering practices - parameterized queries, whitelisting, least privilege, and vigilant logging - are extremely effective. Use the labs (cluster posts) to learn hands-on, and treat this pillar as your go-to reference for detection and remediation.

References & further reading

- PortSwigger Web Security Academy - SQL Injection labs.

- OWASP - SQL Injection Prevention Cheat Sheet.

- Database vendor security docs (MySQL, PostgreSQL, Microsoft SQL Server).