0-Click Account Takeover via Punycode: How IDNs and String Normalization Break Authentication

A practical, beginner-to-advanced guide explaining how Punycode (IDNs) can enable 0-click account takeover, why it happens, and how developers and defenders can prevent it.

Disclaimer (must read): This article is written for educational and defensive purposes. It explains a real attack pattern (account takeover via Punycode/IDN confusion) so developers, security engineers, and bug hunters can detect and remediate it. Do not use these techniques on systems for which you do not have explicit authorization.

TL;DR

A class of account takeover occurs when an application treats visually similar email addresses (one ASCII, one using Unicode characters) as equivalent due to string normalization or database casting. An attacker who controls a visually confusable Internationalized Domain Name (IDN) can receive password resets, invites, or activation links intended for a real ASCII account - sometimes without user interaction (a 0-click takeover). This post explains why this happens, how to test for it safely, real-world impact, and robust server-side countermeasures.

1 - Introduction: why Unicode matters for authentication

Every web developer learns that email addresses and usernames are sensitive identifiers. We usually assume an email is a unique string the application can rely on for password reset, invites, and account recovery.

But the Internet is multilingual. People use accented letters, non-Latin scripts, and various Unicode characters in domain names and local-parts. To support that, browsers and the DNS use IDNs (Internationalized Domain Names) which convert Unicode domains into an ASCII-compatible encoding called Punycode (it starts with xn--).

Example:

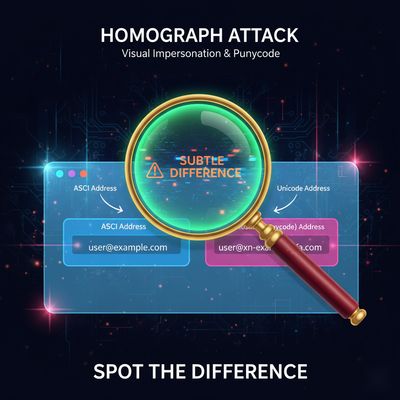

Visually, tàrget.com may look almost identical to target.com. If your application or its database treats those different strings as the same value - due to normalization, collation, or implicit casting - an attacker can exploit that difference to hijack accounts.

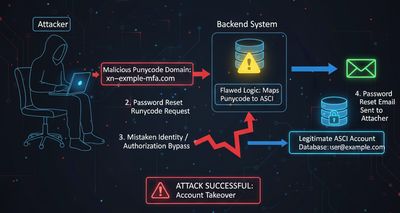

2 - Attack overview: 0-click account takeover using Punycode

Here’s the high-level flow of the attack, conceptualized without using any real researcher names or screenshots:

- Baseline: A legitimate user

alice@target.comregisters and owns the account. - Attacker registers a lookalike: The attacker registers an account with

attacker@tàrget.com(IDN) or otherwise controlsxn--trget-rqa.com. - Application mishandles normalization: The application or DB compares or stores ASCII and Unicode forms in a way that collapses them (e.g., by casting Unicode to ASCII, using a case-insensitive collation that normalizes diacritics, or misusing punycode conversion).

- Triggering account actions: The attacker requests a password reset, invite, or activation for the Punycode address - the system thinks the email "already exists" or (worse) sends the reset link to the attacker-controlled address.

- 0-click takeover: Attacker receives a recovery link and sets a new password; the original ASCII user finds their account controlled by attacker credentials - sometimes without clicking anything on the target account.

The term 0-click is used here because the real user need not perform any action - the attacker obtains control solely via the misinterpretation of email identity.

3 - Where this goes wrong technically

Multiple technical misconfigurations commonly lead to this problem:

3.1 Database collation & normalization

Some database collations perform accent-insensitive comparisons (e.g., treating a and à as equal). If you use such a collation for the email column, queries like WHERE email = ? may match both ASCII and Unicode variants.

3.2 Input normalization & casting

Server code that normalizes or strips diacritics before storage (to "normalize" user input) might unintentionally collapse distinct addresses to the same key. Similarly, code that forcibly ASCII-fied a domain (or used punycode incorrectly) can result in mismatches.

3.3 Punycode / IDN mishandling

If your app internally converts IDN to Punycode in some places but not others (e.g., converting domain during validation but not during storage), two records may collide or actions may be routed to the attacker.

3.4 Email canonicalization bugs in libraries

Some email libraries or frameworks offer canonicalization helpers. If these helpers are misapplied (or used inconsistently between registration, login, and recovery flows), they can create equivalence between different strings.

4 - Practical detection checklist (safe and ethical)

If you’re a developer or authorized tester, follow these steps to detect potential weaknesses:

-

Inventory identity flows: list registration, login, invite, password-reset, activation, and SSO flows.

-

Check email uniqueness constraints: verify database uniqueness and collation on the

emailcolumn. -

Test normalization behavior (safely): use controlled test accounts and check how your app treats:

alice@example.comalice@exämple.com(Unicode domain)alice@xn--exmple-cua.com(Punycode)

-

Try invite/reset with the Punycode version: if the system says “User with this email already exists” when the user doesn’t exist, that’s a red flag.

-

Review logs and headers: check how incoming email addresses are logged (raw vs normalized).

-

Scan dependencies: check if frameworks or libraries perform implicit normalization or punycode conversion.

Important: Only perform these checks on systems you own or are explicitly authorized to test.

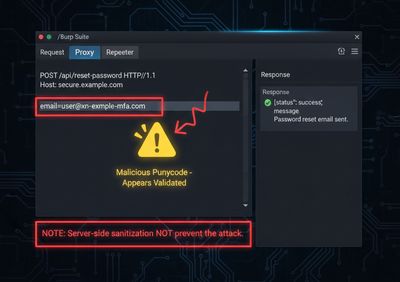

5 - Example safe test (local lab)

Set up a local environment (or a staging environment) and follow this pattern - do not target production customers.

- Create account

alice@demo.com. - Register

attacker@tàrg-demo.com(IDN) using a domain you own or a localhost alias mapped to Punycode. - Attempt to request password reset for the Punycode address.

- Observe whether the reset flow sends mail to the attacker mailbox or shows "already exists" responses.

Example request (sanitized):

If step 3 yields unexpected behavior, your flows need fixing.

6 - Realistic impact scenarios

- Password resets: Attacker receives the reset link and takes account control.

- Invites: Organization invites (e.g., team invites, admin invites) are issued to the Punycode address which maps to the victim account.

- SSO / federated identity: If the identity provider canonicalizes emails differently, SSO flows can be bypassed or confused.

- Account merging and recovery: Any flow that merges accounts or accepts email verification tokens is at risk.

Even if the application uses email verification, an attacker controlling the confusable domain can complete verification steps for the ASCII user if string equivalence collapses.

7 - Why this is sometimes 0-click

The "0-click" nature comes when the attacker solely performs actions on their controlled address and the backend treats that action as applicable to the victim account.

Example: the attacker requests a password reset for tàrget.com (Punycode) - backend maps it to target.com account and sends email to the attacker's address. The attacker's control over the Punycode domain is enough; the victim never interacts.

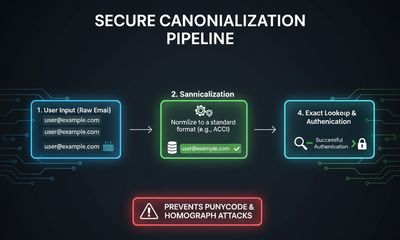

8 - Concrete defensive controls (developer checklist)

Fixes must be applied at several layers: input handling, storage, lookup, and verification.

8.1 Enforce exact string matching for identifiers

Treat email addresses as opaque strings for uniqueness checks: do not apply accent-insensitive collation or other equivalence transforms to the primary key.

8.2 Store canonical forms explicitly and consistently

If you must canonicalize (e.g., lowercase the local part per your policy), do it consistently across all flows and never collapse distinct Unicode codepoints into identical ASCII sequences.

8.3 Keep punycode conversion consistent and explicit

Decide the model:

- Option A: Store raw Unicode email exactly as provided and match exact codepoints on lookup.

- Option B: Always convert domain parts to Punycode for storage and for all lookups - but do this uniformly for registration, login, reset, and invites.

Whichever you choose, apply it everywhere.

8.4 Use strict database collation and constraints

Set the email column with a binary or case-sensitive collation that preserves codepoint differences. Add a UNIQUE constraint to the stored representation used by your app.

8.5 Add proactive blocking for confusable registrations

Optionally, detect visually confusable IDNs and block them, or flag them for manual review. Libraries exist for detecting Unicode homograph sets.

8.6 Harden recovery & invite flows

- Require users to confirm control via existing, previously validated contact channels (e.g., an already-verified backup email or 2FA).

- When invite or reset is requested, do not leak “user exists” vs “user not found” in ways that help an attacker. Use rate-limits and verification tokens.

8.7 Monitor DNS ownership of domains used in emails

If you accept email addresses with domains that are registered/controlled by an attacker, consider DNS verification checks for critical flows (invites, org admin changes).

9 - Sample safe remediation code patterns

A simple pseudocode pattern: canonicalize consistently and check strictly.

Note:

idna_encodeperforms a strict IDNA/Punycode conversion. Use well-tested libraries (e.g., Pythonidnapackage, Nodepunycode).

10 - Detection & monitoring suggestions (Ops)

- Alert on reset/invite anomalies: If password resets or invites use domains that differ only in confusable characters, flag for review.

- Rate-limit recovery attempts per domain and per account.

- Log the raw submitted string and canonicalized key so cross-checks are possible during incident analysis.

- Use canary domains: If you notice a surge of registrations for visually similar domains, investigate.

11 - Responsible testing & disclosure guidance for hunters

If you discover this issue on a third-party service:

- Stop after verifying reproducibility on a test account.

- Do not attempt to exfiltrate or exploit real user data.

- Record sanitized evidence (request/response pairs, timing, and control domain ownership proof).

- Report to the vendor’s security contact or bug bounty program with PoC and remediation suggestions.

- Allow vendor adequate time to patch before public disclosure.

Vendors take these flaws seriously; many programs pay bounties for account takeover chains.

12 - Table: Quick checklist for teams

| Area | Action |

|---|---|

| Input handling | Decide canonicalization policy (Unicode vs Punycode) and apply everywhere |

| Storage | Use binary-sensitive collation; enforce UNIQUE constraint on stored key |

| Lookup | Use exact-match lookups on the canonical form |

| Recovery flows | Require multi-factor verification for critical flows |

| Monitoring | Log raw vs canonicalized inputs; alert on homograph patterns |

| Policy | Include homograph IDN checks in onboarding/registration rules |

13 - Real-world mitigation approaches and trade-offs

- Block suspicious IDNs: Effective but may deny legitimate international users. Consider whitelists or risk-based review.

- Normalize to Punycode globally: Simpler developer model but requires robust IDNA handling. Must be applied consistently to avoid gaps.

- Require secondary verification for critical actions: Strong but increases friction.

- User education: Warn users about potential homograph phishing - useful but insufficient alone.

Balance usability and security - for highly sensitive apps (finance, identity providers), prefer stricter controls.

14 - Final thoughts

Punycode and Unicode homograph issues are subtle and easy to miss because they live at the intersection of internationalization, DNS, and authentication. The most important rule is consistency: choose a canonicalization and comparison strategy and apply it uniformly across registration, login, invites, password reset, and SSO. Combine that with robust logging, rate-limiting, and multi-factor protections for the highest-risk flows.

By treating email addresses as precise, policy-driven identifiers (not loose, human-friendly strings), organizations can prevent entire classes of account takeover attacks - including 0-click scenarios where the victim never interacts.

References & further reading

- IDNA (Internationalized Domain Names for Applications) RFCs and libraries.

- OWASP guidance on authentication and account recovery best practices.

- PortSwigger research and lab exercises on IDN/homograph issues.

- Vendor advisories on Punycode homograph phishing.

Published on herish.me - building actionable, beginner-friendly security guides that developers actually use.