400 Bad Request that earned $$$ - Document-name disclosure via IDOR

How a 400 error exposed workspace and document names due to an IDOR in a document-viewer API - step-by-step reproduction, impact, and defenses.

Disclaimer

This article is written for defensive and educational purposes. All testing described was performed only with authorization or in a controlled context. Never attempt unauthorized access to systems you do not own or have explicit permission to test. The examples below are redacted and safe - they show request/response structure to explain root cause and remediation.

Introduction

APIs often reveal more than developers expect - not because of a classic SQL injection or broken authentication, but because of seemingly innocuous error messages. During a recent assessment Researcher came across a document-viewer API that responded to malformed annotation saves with a 400 Bad Request carrying a human-readable error that included the document name. Chaining this with a simple ID brute-force technique allowed discovery of workspace names and document names that should have remained private.

This post walks through how Researcher discovered it, how to reproduce the behavior safely, why it matters, and - most importantly - how teams should fix this class of leakage so it never happens again.

Understanding the target and the bug at a glance

The application exposes a document viewer API for collaborating on documents inside named workspaces. A POST endpoint handles saving annotations and returns structured JSON on success and failure. Crucially, when supplied with a WorkspaceID and DocumentArtifactID that the caller does not have access to, the API returns an error JSON whose CustomErrorMessage contains the document name. When that happens, an authenticated attacker can enumerate WorkspaceID values and then probe DocumentArtifactID values to recover internal names.

Why this is problematic:

- Document names are often sensitive (client names, PII hints).

- Workspace names may reveal business relationships or internal project names.

- Error-based enumeration is trivial to automate (ffuf/ffuf-style fuzzing).

- There were no effective rate limits on the discovery endpoint in this case.

Step 1 - Initial reconnaissance (authenticated)

This issue requires an authenticated session. During triage Researcher logged in as a normal user (non-admin) to mimic a real-world attacker who already has valid credentials but should not see other organizations’ artifacts.

My reconnaissance checklist:

- Map API endpoints around the Document Viewer.

- Identify annotation/save endpoints that accept JSON payloads.

- Check whether error messages are redacted or contain friendly strings.

- Test error responses for leaked metadata.

Researcher found the following relevant endpoints during mapping and proxy inspection:

POST /Private.Rest/API/private-processing/v1/workspaces/FUZZ/data-sources/0/field-mappings/private- helpful to brute-force the organization/workspace existence.POST /Private.REST/api/Private-DocumentViewer/v2/workspaces/{WorkspaceID}/annotations/save- the annotation save endpoint that returnedCustomErrorMessagevalues containing document names.

Step 2 - Safe, ethical fuzzing to find a valid WorkspaceID

To avoid noisy, unauthorised tests, do this only inside scope and with credentials you are permitted to use. The pattern is:

- Attempt to trigger an identifiable error message when the WorkspaceID does not belong to the logged-in user.

- Identify phrases in the returned JSON that include workspace identifiers.

Example request used for discovery (redacted for safety):

If the fuzzed FUZZ value corresponds to a workspace that exists but you cannot access, the server returned a 500 Internal Server Error with a message similar to:

That response is useful because it confirms the workspace exists (and returns an ID in the message). From there you can target the DocumentViewer endpoint.

Important: This kind of probing is sensitive. Only run it under authorization and throttle your requests.

Step 3 - Probing the annotation save endpoint to reveal workspace names

With a valid WorkspaceID identified (in the above example: 1028172), the annotation save endpoint accepted an annotations JSON array. Submitting an annotation for a document you don’t have access to should fail - but the server’s failure message surprisingly included the document’s human-friendly name.

Example payload:

For certain DocumentArtifactID values the server responded with a JSON error containing the document name. Example response pattern:

In other cases the response included the workspace name string inside the message, for example when saving annotations to some folders. The two screenshots Researcher captured (redacted) show the different DocumentArtifactID values and the returned document names that confirm the exposure.

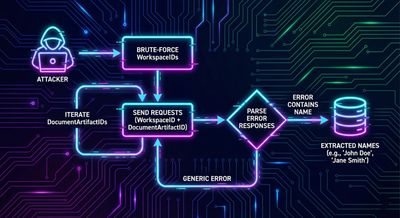

Step 4 - Automating enumeration safely (how an attacker would scale)

The vulnerability becomes high-impact when automated. An attacker with a valid user cookie can:

- Enumerate

WorkspaceIDvalues (using a safe wordlist or ranges). - For each discovered workspace, iterate

DocumentArtifactIDvalues and submit the annotation payload above. - Parse

CustomErrorMessagestrings for visible document/workspace names and store the results.

A pseudo-automation approach (ethical use only):

Because the API returned different HTTP codes and messages (500 vs 400) depending on the scenario, the enumeration script can use response status and body text to confirm existence and capture names.

Defensive note: rate limiting, strong access checks, and sanitized error content would stop this.

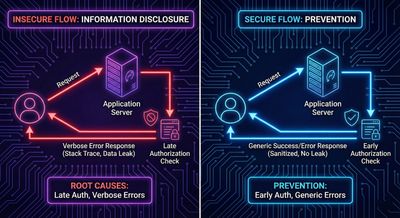

Step 5 - Root cause analysis (why this leak occurs)

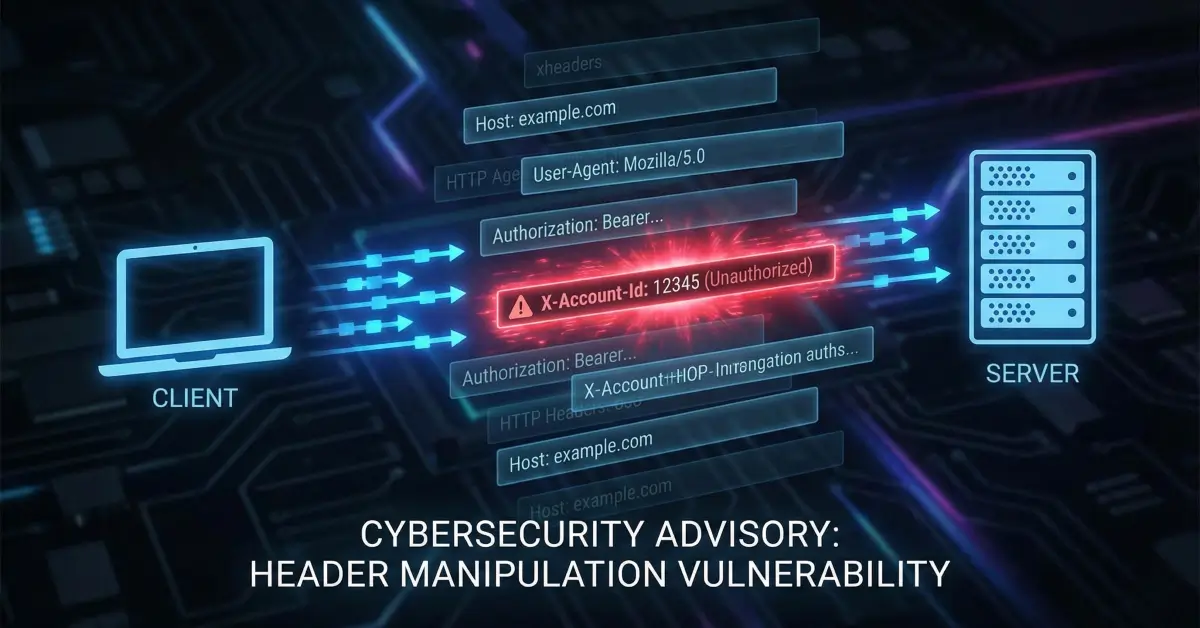

The root causes combine two developer-side mistakes:

- Weak authorization checks: the server attempts to process the annotation before performing an ownership check, leading to error paths that expose metadata.

- Verbose, unauthenticated error messages:

CustomErrorMessagestrings include human-friendly names for debugging or UX reasons, but these are not sanitized when returned to unauthorized callers.

When combined, an attacker can elicit the server into disclosing internal strings simply by triggering error conditions.

Step 6 - Impact assessment

Even though the payloads do not directly download document contents, leaking document and workspace names can be sensitive:

| Impact | Why it matters |

|---|---|

| Confidentiality loss | Document names may include client names, PII, case IDs |

| Reconnaissance | Names help an attacker choose high-value targets for social engineering |

| Regulatory exposure | PII leaks can lead to GDPR/other compliance concerns |

| Business risk | Project or client names can reveal business relationships |

Depending on how teams name documents (for example, including full client names, identifiers, or case numbers), the severity can range from moderate to high. In the reported case the program triaged and resolved the issue and the researcher received a bounty.

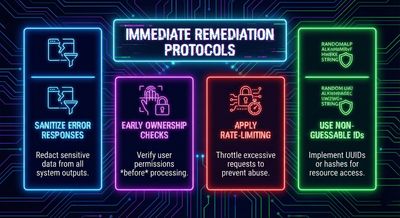

Step 7 - Immediate remediations (what to patch now)

If you maintain a document viewer API, prioritize the following fixes right away:

1. Sanitize error messages

Do not return human-friendly object names in error payloads visible to unauthorized users. Return generic error codes/messages and log details server-side.

2. Enforce ownership checks as early as possible

Before attempting to process or validate payloads that reference WorkspaceID or DocumentArtifactID, verify the caller’s authorization. Reject unauthorized access with a generic 403/404.

3. Use non-guessable identifiers where appropriate

If possible, adopt UUIDs or other non-sequential identifiers that make enumeration harder.

4. Rate limit and monitor enumeration patterns

Apply request throttling per logged-in user or IP and trigger alerts on high-volume enumeration behavior.

5. Do not use verbose debug strings in production

Developer-friendly messages belong in logs, not in client-facing responses.

6. Redaction & logging

If a server needs to include a context message for downstream systems, ensure that logs keep the sensitive name while the API response returns only a generic token the developer can correlate.

Step 8 - Longer-term hardening & testing

Beyond immediate fixes:

- Periodic scanning: run automated scans looking for error-message leakage across APIs.

- Threat modeling: consider naming conventions and what metadata is safe to expose.

- Secure development training: teach devs the dangers of informative errors.

- Response validation: ensure test suites assert that error bodies do not contain object names.

- Incident playbooks: prepare processes for disclosure and rapid patching when leaks are found.

Troubleshooting & common pitfalls during remediation

Teams sometimes make mistakes while fixing this issue:

- Fixing only the annotation endpoint but not other endpoints that also embed names in errors.

- Returning generic HTTP codes but still embedding metadata inside nested JSON fields.

- Overly broad 404s that break legitimate functionality - prefer 403 for unauthorized, 404 for not found depending on design.

- Forgetting to remove verbose logging to client when moving code from staging to production.

A careful regression test across the entire DocumentViewer surface is essential.

Responsible disclosure & reward outcome

When responsibly disclosed to the vendor, the issue was triaged and patched. The program confirmed the root cause (error message leakage + insufficient authorization checks) and applied fixes across API layers. The researcher was rewarded with a bounty. That outcome - patching, acknowledgement, and reward - is how we keep systems safer.

Final thoughts

This IDOR variant is deceptively simple: it is not an SQLi or broken auth flow, but error-message leakage plus predictable IDs. Teams can prevent similar findings by sanitizing responses, performing ownership checks early, and making enumeration difficult via unpredictability and rate-limiting.

If you maintain APIs that reference business-sensitive objects, treat error content as sensitive too - never leak metadata to unauthorised callers.