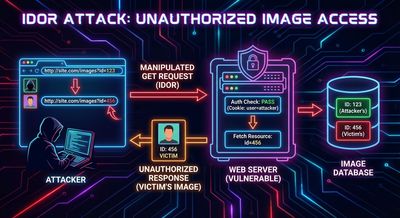

How a Simple Image Download Feature Became a Full IDOR Enumeration Attack

A real-world bug bounty case study showing how a simple image downloader exposed user data through predictable identifiers, leading to an enumeration-based IDOR.

⚠️ Disclaimer

This write-up is educational and defensive. All testing described was performed with permission or on controlled accounts. Do not test targets you do not own or for which you lack explicit authorization.

Introduction

Ordinary features are where the best bugs hide. A background-image removal tool, a temporary storage bucket, a simple “download processed image” link - none of these sound dangerous on their own. But when an application uses predictable filenames and serves files without ownership checks, the result is a classic Insecure Direct Object Reference (IDOR) with realistic, automated exploitation potential.

This post reconstructs a real bug bounty case: how an image download endpoint with a single docName parameter turned into a scalable IDOR. The researchers turned a casual curiosity into a repeatable proof-of-concept by reverse-engineering filename structure, building a controlled enumerator, and validating the ability to retrieve other users’ images.

This is written in a neutral, third-person style suitable for engineering teams, bug hunters, and security reviewers. It focuses on reproducible defensive lessons rather than playing the role of a how-to for attackers.

Background: the feature and the initial finding

The application provided an endpoint to download processed images:

From casual testing the endpoint returned the requested file directly. Two simple experiments showed the problem’s contours:

- Upload image under Account A - get filename A.

- Upload image under Account B - get filename B.

- Substitute filename B into the download URL while authenticated as Account A - the server returned Account B’s image.

Conclusion: the server did not verify that the requesting user owned the docName resource.

At this point the bug was an IDOR candidate. Triage asked a reasonable question: “How would an attacker obtain other users’ filenames?” Answering that required pattern analysis and enumeration.

Step 1 - Pattern discovery: what is docName made of?

To move from a simple IDOR into an exploit-ready case, the researchers focused on filename patterns. By uploading multiple images and collecting filenames, they identified a stable template:

Typical example:

Breaking down the components:

- id - 6-digit decimal, sequential (incrementing with uploads/accounts).

- username - the account’s display name as provided at signup.

- unix_timestamp - numeric seconds since epoch, matching upload time.

Each component is predictable (sequential id; known or guessable username; timestamp in a bounded window). That combination removes the “random secret” assumption and makes brute-forcing feasible.

Step 2 - Designing an enumeration strategy

With the pattern identified, the goal was to prove real-world feasibility without causing harm.

Constraints and assumptions:

- Files persist for 30 days. This gives time windows for enumeration.

- IDs increment globally (or per tenant) - enabling backward enumeration from recent uploads.

- Usernames are often discoverable or guessable (public profiles, marketing pages, simple derivation).

Enumeration approach:

- Start with recent high ID values and iterate downward (IDs likely to correspond to recent uploads).

- Generate username candidates: known public names, simple transformations (lowercase, remove spaces), and common names for the site.

- Create timestamp windows: assume upload occurred within a plausible range (e.g., last 72 hours) and iterate timestamps at coarse granularity first, refine when needed.

- Lightweight checks: send HTTP

HEADor smallGETrequests to validate availability without downloading massive content. Treat200 OKas valid and404as not found. Rate-limit and respect service constraints.

This approach trades breadth for targeted, logic-driven probing to minimize noise and false positives.

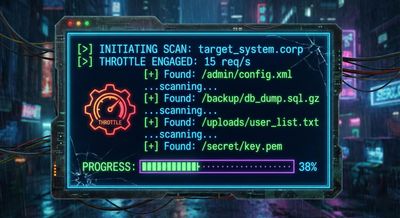

Step 3 - Implementing the controlled prover (safe PoC)

The researchers wrote a small enumerator script (conceptual flow shown here; do not run against in-scope systems without permission):

The script demonstrates responsible searches by focusing on small windows and adding throttling. The real testing used more sophisticated heuristics to reduce requests and false positives and to avoid impact.

Step 4 - Practical barriers, false positives & tuning

Enumeration is noisy if performed naively. The team encountered and mitigated several issues:

- False 404/200 behaviors: some filenames returned 200 but were placeholder images; validating content-length and HTTP headers helps.

- Timestamp resolution: matching exact second can be hard; using minute-level windows and then refining produced better results.

- Username normalization: spaces, case, diacritics - canonicalization rules on server side required testing different transformations.

- Rate limiting & detection: aggressive scans triggered defenses; the final PoC respected rate limits and included backoff.

After several iterations, the PoC reliably discovered real, accessible filenames belonging to other accounts - validating the attack path.

Impact assessment

Why is this more than a “toy” bug?

- Sensitive content: user-uploaded images can contain faces, IDs, documents - high-value PII.

- Volume: with automation and thirty-day retention, thousands of images can be enumerated.

- Ease of exploitation: attacker needs no special privileges, only predictable patterns and a legit account.

- Chaining potential: exposed images could be used for targeted phishing, blackmail, or social engineering.

CVSS-style considerations (illustrative):

- Authentication: required (low barrier if account creation is easy).

- Complexity: low–medium (pattern analysis + automation).

- Impact: High on confidentiality for exposed images.

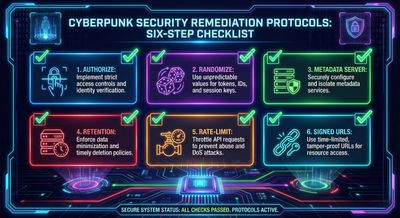

Remediation checklist (developer playbook)

Fixes should be layered.

-

Authorize every download

- Do not accept client-supplied filenames as an authorization token. Map server-side IDs or tokens to owners and enforce checks.

-

Use unguessable identifiers

- Replace predictable filenames with cryptographically random names (UUIDs or random hash strings) unrelated to user data.

-

Keep file metadata on the server

- Store

{ file_id, owner_user_id, original_filename, upload_time }and serve only viaGET /download/<file_id>after authorization.

- Store

-

Shorten retention when possible

- Only retain files as long as necessary and purge expired objects promptly.

-

Rate-limit and monitor

- Detect patterns of enumeration: many 404s for sequential IDs or timestamp sweeps.

-

Content access tokens

- For temporary public access, generate signed, time-limited URLs (one-time tokens) that map to a specific owner and expire quickly.

-

Avoid embedding sensitive data in filenames

- Never include usernames or PII inside storage object names.

For bug hunters: responsible reporting tips

When you report this class of issue, include:

- Clear reproduction steps using test accounts (never include real victim data).

- Evidence of pattern predictability (non-sensitive sample filenames from your own uploads).

- A concise impact statement: number of objects, retention window, type of likely content.

- Suggested remediation (server-side mapping, random IDs, authorization checks).

Polite, concrete reports accelerate triage and fixes.

Closing thoughts

Boring endpoints can be dangerous endpoints. This case demonstrates how predictable identifiers + lax authorization create a high-confidence, automatable IDOR. The fix is conceptually simple - authorize, randomize, and minimize exposure - but it requires discipline in design and implementation.

For defenders: treat every user-controlled identifier as untrusted.

For hunters: patient pattern analysis and respectful, well-documented reporting are the keys to turning a curiosity into impact.

References & acknowledgements

- Case study reconstructed from an anonymized bug bounty write-up and the researcher’s responsibly disclosed report.

- General IDOR guidance: OWASP Top 10 - Broken Access Control.

- Practical tips based on common secure file-handling best practices.