Lab: SQL injection UNION attack - determining number of columns returned by the query

Step-by-step walkthrough: using a UNION-based SQL injection to determine the number of columns returned by a query. Beginner-friendly, with payloads, troubleshooting and defensive guidance.

⚠️ Disclaimer

This write-up is for educational and defensive purposes only. Perform these techniques only in legal, controlled environments such as PortSwigger labs or your own test systems. Do not attempt attacks on systems you do not own or have explicit permission to test.

TL;DR

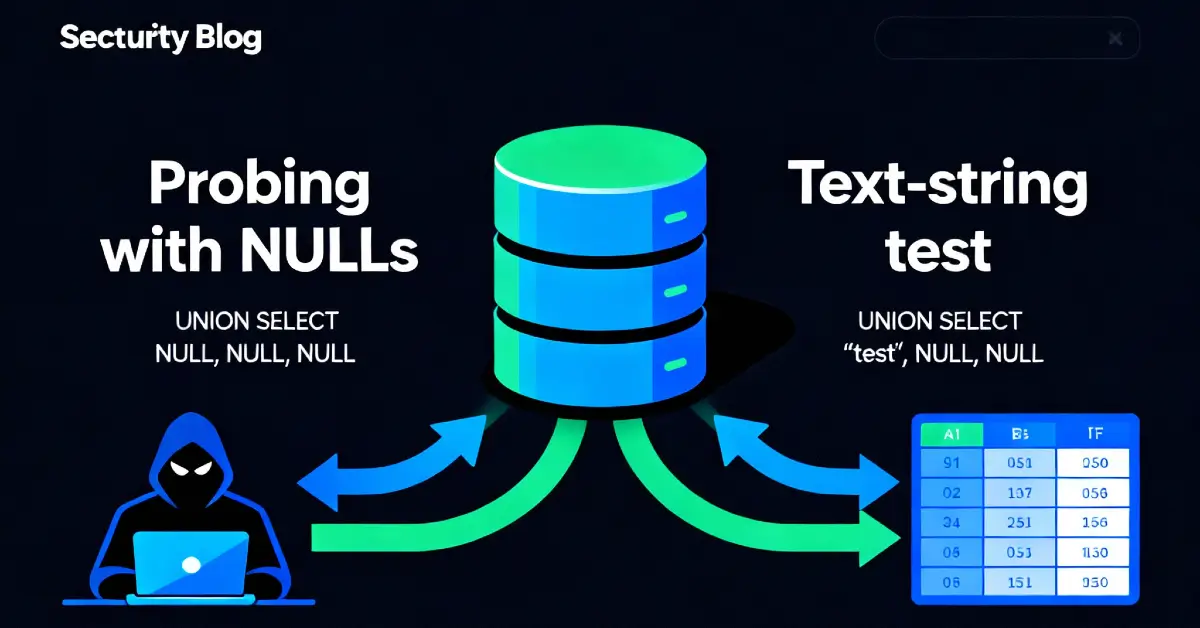

This lab teaches a classic UNION-based technique: determine how many columns the original query returns by injecting UNION SELECT NULL,NULL,... until the server accepts the injected result. I intercepted the product filter request, replaced the category parameter with a UNION SELECT probe, and incrementally added NULL placeholders until the application stopped erroring. Final successful payload used in the lab was:

This article is a full walkthrough: reconnaissance, exact payloads, how to confirm which columns are text-capable, practical troubleshooting, defensive guidance for developers, and real-world examples that show why this technique matters.

For background theory on SQLi and UNION techniques, see our pillar: The Ultimate Guide to SQL Injection (SQLi).

1 - Lab objective & initial observations

Lab goal (PortSwigger): Use a UNION-based SQL injection to determine the number of columns returned by an application's query. Usually this is an early step before extracting data via UNION SELECT.

From the UI I noticed a product listing filtered by category. That filter is a classic injection surface - categories are often reflected in queries like:

If the app concatenates user input into SQL, appending a UNION SELECT lets us combine our own row with the original result set - but the UNION requires the same number of columns/types. The lab is solved when we find the correct number of columns and the response includes the injected values.

Quick reconnaissance checklist I followed:

- Identify the request that controls category filtering.

- Confirm the parameter is reflected or used server-side.

- Try a gentle

UNION SELECT NULLprobe to trigger an error or reveal behavior. - Incrementally add

NULLs until the error disappears.

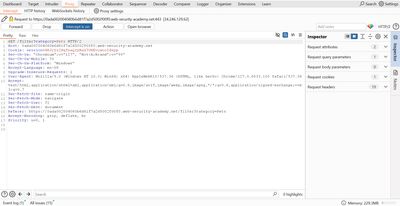

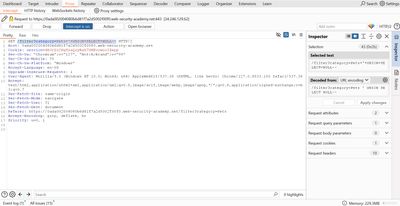

2 - Capture the vulnerable request

I used Burp Proxy to record a normal browse that filters products by category. The (sanitized) request pattern looked like this:

The page returned a product list corresponding to the Pets category. That confirmed the category parameter controlled which rows the app queried - an ideal place for a UNION probe.

Beginner breakout - why GET is fine here:

Even though GET parameters are visible in the URL, they still reach the server and can be used to demonstrate SQLi in labs. Always treat both GET and POST parameters as untrusted input.

3 - First test: baseline UNION NULL probe

The minimal UNION payload is a single NULL column added via UNION SELECT. I injected the following by editing the category value in the captured request (URL-encoded in a browser):

Why NULL? It is a safe placeholder that won’t trigger type conversion problems. If the number of NULLs doesn’t match the original query’s column count, the DB returns a column-mismatch error (or the app shows an error). That tells us we need more columns.

When I sent the single-NULL probe I observed an error response - the application could not union a single column with the original result (column count mismatch). That’s expected and useful.

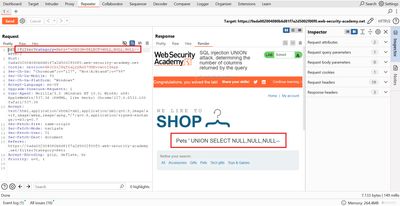

4 - Iterative approach: add NULLs until the error disappears

This step is straightforward but requires patience. I appended additional NULL values to my UNION SELECT probe until the app accepted the injection and returned a page that included the injected row.

Sequence I used (URL-encoded / space-escaped form):

Each request increases the NULL count by one. In this lab, the successful probe was:

When that request was sent, the error disappeared and the response included additional content consistent with our UNION row - the application accepted a UNION SELECT with three columns, so the original query returned three columns. That confirmed the required column count.

Why this works: UNION requires both queries to return the same number of columns; adding NULL placeholders lets us match that number without knowing column names or types.

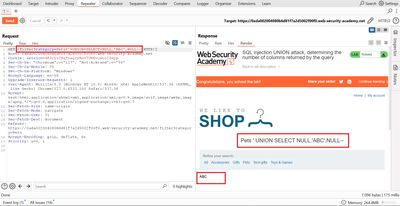

5 - Confirming which column can show text (finding a text-capable column)

Knowing the column count is step one. Next, to extract data we must find a column that is rendered as text on the page (a text sink). A common method is to replace one NULL with a string literal and see if it appears in the response.

Example test (after confirming 3 columns):

If the page contains ABC, that column is text-capable and can be used to return usernames, product names, or other strings. If ABC doesn't appear, try the string in the second or third position:

Pick the column that reflects output. In many labs one or more columns will be rendered directly into the HTML template and thus show our injected text.

Beginner breakout - string quoting:

When injecting string literals into URLs, URL-encode single quotes (' -> %27) or wrap the string using the database's accepted syntax. In lab contexts, simple quoted strings usually work if the UNION is allowed.

6 - Practical example: moving from NULL to extraction

Once a text-capable column is identified, you can extract data. For example, to list usernames from a users table (lab or authorized test only):

You might need to refine the payload (schema name, table name) or use LIMIT and OFFSET to extract rows one-by-one. In this lab the goal was only to determine the column count - but the exact same technique powers data extraction in further labs.

7 - Troubleshooting common issues

While the approach is simple, several pitfalls are common. Here's how I handled them:

- Application returns a generic error page: Inspect server logs or the raw HTTP response. Sometimes error details are hidden in HTML comments or response headers.

- Filtering / WAF rules: If the app blocks

UNIONorSELECT, try variants (UN/**/ION, case changes, or SQL comments). Only use these in authorized labs. - Type mismatch errors: If

NULLstill causes issues, tryCAST(NULL AS VARCHAR)or database-specificNULL-compatible expressions (advanced - not needed in most labs). - Quoted contexts: If the vulnerable parameter is inserted inside quotes in the original query, ensure the injected payload closes the quote correctly (e.g.,

'+UNION+SELECT+...--used here closes a preceding'). - Error disappears but no visible injected content: The app may suppress our row or render it in an unexpected location. Use a unique string like

'XYZ123'to test visibility, or inspect the full HTML source for hidden echoes.

Why not brute-force extraction first? Finding the right column count reduces guesswork and avoids noisy extraction attempts that may trigger alarms.

8 - Defensive perspective (how to prevent UNION-based exploitation)

This section is critical for developers and ops teams.

8.1 Parameterized queries & ORM usage

- Never build SQL by concatenating user input. Use parameterized queries or ORM query builders which separate data from code.

- ORMs often make

UNIONmisuse harder; where raw SQL is necessary, parameterize thoroughly.

8.2 Principle of least privilege

- Ensure the DB account used by the web app cannot access unnecessary tables (e.g., system tables, admin schemas). Limit SELECT permissions to only required tables/columns.

8.3 Input validation & whitelisting

- Validate filter parameters against an allowed set (e.g., known categories). If categories are fixed (Pets, Electronics), don't pass raw text to SQL - map to internal IDs instead.

8.4 Error handling & hiding DB details

- Avoid exposing DB error messages to users. Generic error pages reduce the attacker’s ability to infer column structures.

8.5 WAF & detection (defense-in-depth)

- Set WAF rules to flag

UNION,SELECTin parameters that normally accept short values. - Monitor for requests that include SQL-like sequences in query strings.

8.6 Testing & CI

- Add automated tests that try

UNION SELECT NULLprobes in staging to detect parsing mismatches between front-end and DB.

9 - Detection & logging recipes (practical alerts)

- WAF rule: Alert on request parameters containing patterns like

UNION SELECT NULL,UNION SELECT %27, or unusual sequences of commas andNULL. - SIEM detection: Correlate sudden increases of

NULL-probing requests with other anomalous behavior (scans from single IP). - Application logs: Log suspicious parameter values and track sources. If a filter parameter suddenly contains commas or SQL keywords, flag it.

- RUM / frontend telemetry: If a normally static filter page begins returning unexpected content or errors, trigger an investigation.

10 - Real-world examples (why column-count techniques matter)

Example A - Data leakage through union enumeration

In a real e-commerce incident, researchers found that a product filter accepted UNION probes. Attackers enumerated columns and later extracted vendor configuration that revealed API keys stored in another table. The site used concatenated SQL for filters - a fix involved mapping categories to numeric IDs and parameterizing every query.

Example B - Third-party integrations exposing admin data

A poorly written analytics endpoint joined product data to admin notes. Attackers discovered the column count and used UNION extraction to pull admin comments that contained internal server names, directly enabling further lateral attacks.

Example C - Automated scanners and noisy extraction

Automated tools often use the same NULL-probe approach. Sites that failed to detect these probes were later scraped by bots that extracted large volumes of product and user metadata. A detection rule catching repeated NULL probes from a single IP stopped the bot quickly.

These real cases show: finding the column count is not just an academic exercise - it's the gateway to broader data extraction.

11 - Why not other approaches (short guidance)

- Why not start with

UNION SELECT users.username,...immediately? Without knowing the column count and a text-capable column, yourUNIONwill likely error. Start withNULLprobes to minimize noise. - Why not brute-force with

sqlmapalone? Automated tools are powerful but noisy. Manual probing gives control, reduces false positives, and teaches the underlying mechanics - ideal for labs and careful assessments.

12 - Suggested practice steps (what you should do next)

- Reproduce the lab flow and practice incrementally adding

NULLplaceholders until success. - Once you find the column count, replace a

NULLwith a test string to find a visible column. - Use

UNION SELECTwith a safe, limited query to validate your control (e.g.,SELECT 'TEST', NULL, NULL). - Move to extraction only in the lab or in authorized engagements; always avoid data exfiltration on production systems without permission.

13 - Final thoughts

This UNION-null probing technique is a foundational skill for web-security practitioners. It’s low-noise, reliable, and teaches you how queries are structured. Defenders can stop this by adopting parameterized queries, strict input whitelists for filters, and proactive detection rules for UNION-style probes.

References

- PortSwigger Web Security Academy - SQL Injection (UNION) labs.

- OWASP - SQL Injection Prevention Cheat Sheet.

- RFC and DB vendor docs for SQL syntax (for advanced casting / comment behavior).