Outsmarting the Firewall: XSS in URLs Explained (Educational Purpose Only)

Practical, pentester-focused techniques for why XSS in URLs still works and how WAFs can be bypassed - defensive advice included.

Disclaimer (must-read):

This article is written for educational purposes and defensive learning only. Do not use these techniques against systems you do not own or have explicit permission to test. Always follow responsible disclosure and legal rules. The goal here is to help defenders understand attack patterns so they can build better protections.

TL;DR

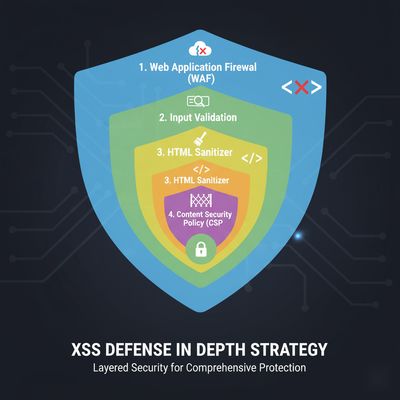

WAFs help - but they are not a substitute for proper input handling. Attackers often use encoding, obfuscation, browser quirks, and context switches (URL → HTML → event handler) to get XSS payloads across the WAF boundary. This post is a pentester-friendly, defensive-minded walk-through of those techniques and, critically, how to mitigate them.

1 - Why URLs are a tempting XSS vector

Modern apps accept data from many places: POST bodies, headers, cookies - and URLs. URLs are convenient for attackers because:

- They are easy to craft and share.

- Many applications reflect parts of the URL (query string, fragment, path) into pages, logs or client-side code.

- URL-encoded characters can hide suspicious tokens from naive filters.

- Some apps mistakenly insert raw URL contents into HTML without escaping.

From a defender’s POV, query parameters and path segments are untrusted input just like form fields. Treat them accordingly.

2 - WAFs: what they do well, and where they fail

WAFs perform pattern matching, heuristics, and sometimes ML-based detection. Strengths:

- Block common, high-volume payloads (

<script>,alert(). - Prevent obvious attacks (known exploit signatures).

- Rate-limit and block noisy bots.

Weaknesses:

- Many WAFs decode payloads only once or inconsistently. Browsers may decode multiple times.

- Case-sensitive implementations or incomplete canonicalization can be bypassed.

- WAFs often perform lexical checks but cannot fully emulate browser HTML parsing quirks.

- Business logic and context-sensitive reflection are outside the scope of most WAF signatures.

In short: WAF = useful layer, not the only layer.

3 - Practical XSS-in-URL evasion techniques (pentester's catalog)

Below are proven techniques grouped by type. Each is followed by defensive advice.

A - Encoding and double / layered encoding

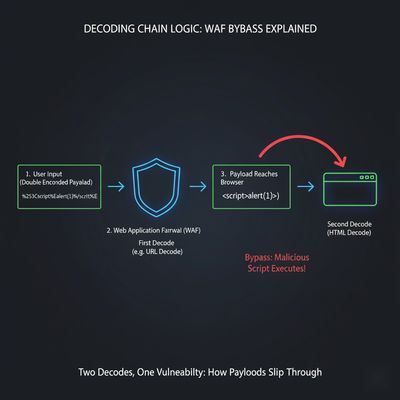

WAFs frequently canonicalize input once. Attackers can double-encode so the WAF decodes once but the browser decodes twice.

Example - raw payload (likely blocked):

URL-encoded version (sometimes blocked):

Double-encoded (may slip through):

Why it works: The WAF decodes %25 to % (one layer) then sees %3C... but treats it as literal because it may not decode again. The browser decodes twice and executes.

Defense:

- Canonicalize fully server-side (apply the same full decode the browser performs) before filtering.

- Deny suspicious sequences after canonicalization.

- Avoid reflecting raw input; always escape for the correct context (HTML, JS, URL).

B - Case switching and mixed-case tokens

Some WAFs match only lowercase signatures. Mixed-case can bypass naive checks.

Example:

Why it works: Matching is literal in some rulesets.

Defense:

- Normalize case (to lowercase) then inspect canonicalized data.

- Use context-aware parsers instead of naive regexes.

C - Breaking up keywords (character injection / concatenation)

Split keywords so signature matchers fail; the browser reconstructs them.

Examples:

Insert whitespace / control characters:

String concatenation inside a JS context (when reflected into inline JS):

(If the URL is reflected into JS source, attackers can build the token dynamically.)

Why it works: WAFs often search for alert( literal; injected characters break the literal string.

Defense:

- Escape data for the JavaScript context (use

JSON.stringify()-like encoding). - Disallow control characters in inputs or normalize them out.

- Apply a strict context-aware sanitizer.

D - Using alternative execution contexts (event handlers, SVG, data URIs)

If <script> is blocked, other elements can execute JS via event handlers or SVG.

Examples:

Image onerror:

SVG animation:

Data URI redirect to JS (older browsers or misconfigured contexts):

Defense:

- Escape and/or strip event attributes if user-supplied data is allowed in element attributes.

- Use a strict Content Security Policy (CSP) restricting

script-srcand disallowingunsafe-inline. - Avoid dangerously setting

innerHTMLwith unsanitized content.

E - Browser parsing quirks & broken markup tricks

Browsers often auto-correct malformed HTML; WAFs typically do not emulate that behavior. Attackers exploit this gap.

Example (broken script tag nested in SVG):

Why it works: Browser fixes nested / broken markup and ends up executing the intended script; static WAF regexes may not spot the obfuscated sequence.

Defense:

- Use an HTML sanitizer library (DOM-based) that understands real browser parsing rules (e.g., DOMPurify).

- Sanitize on server side before storing or reflecting input.

F - Context-swapping: URL → JS string → DOM insertion

Attackers look for flows where a URL parameter ends up inside a <script> block or inside innerHTML. Example chain:

- Parameter inserted into JS variable via server-side templating:

var p = ""; - Later used with

document.write(p)orinnerHTML.

Attack:

If templating is naive, the injected ");alert(1);// will close the string and execute.

Defense:

- Avoid server-side templating that inserts raw user input into JS contexts.

- Use templating helpers that auto-encode for the correct context (

escapeJs()). - Use

textContentor safe DOM creation APIs instead ofinnerHTML.

G - Parameter pollution and duplicate keys

Some frameworks take the first or last occurrence of a parameter. Attackers send multiple values to confuse server-side parsers.

Example:

Defense:

- Normalize parameters defensively (allow only a single canonical value or validate list formats).

- Reject overloaded or duplicated parameters in security-sensitive endpoints.

4 - Detection strategies (for defenders and blue teams)

If you're defending an app, detect these patterns proactively.

- Canonicalization + normalization pipeline: Always fully decode URL-encoded input the same way the browser does before logging and filtering.

- Grep for suspicious characters in logs:

%3C,%3E,%25,onerror=,<svg,javascript:, nested encodings. - Behavioral detection: Monitor for repeated weird encodings or abnormal request lengths to sensitive endpoints.

- Grepping reflected responses: After an input is accepted, check whether it appears unescaped in the HTML response (automated unit test can do this).

- CSP reporting: Enable CSP with

report-urito detect attempted inline execution on production (deploy carefully).

5 - Fixes and secure-by-design practices

This is the most important section for teams. WAFs are a band-aid; true security requires design and coding best practices.

-

Contextual output encoding - Always encode for the target context:

- HTML text: escape

<,>,&,"etc. - HTML attribute: additionally escape quotes.

- JavaScript: escape characters that break string literal contexts.

- URL: use

encodeURIComponent()and validate.

- HTML text: escape

-

Prefer text APIs over HTML APIs - Use

textContent/setAttribute/ DOM creation methods; avoidinnerHTMLunless sanitizing with a safe library. -

Use a modern HTML sanitizer - DOMPurify (for browsers/server-side Node), OWASP Java HTML Sanitizer, or equivalent.

-

Implement strong CSP - block

unsafe-inlineand restrictscript-srcto trusted origins, addstrict-dynamicif appropriate. -

Whitelist input where possible - validate parameter formats (e.g., email, integer, slug) instead of filtering by blacklists.

-

Server-side canonicalization and validation - decode inputs fully and then validate. Do not rely on client-side checks.

-

Regression & unit tests for reflective endpoints - automated tests should flag when user-supplied input appears raw in a page.

-

Security code review focused on contexts - check template insertions into JS, CSS, attributes, and HTML.

6 - Ethical testing checklist (if you have permission)

If you are performing authorized testing:

- Limit requests-don’t spam production.

- Use dedicated test accounts.

- Prefer staging environments.

- Provide clear reproduction steps and PoC in your report.

- Suggest mitigations, not just the issue.

- Respect data privacy-don’t leak sensitive info in reports.

7 - Example payloads (safe, non-executing examples)

Below are illustrative payloads. These are encoded to show patterns and not intended to be run on random sites. Use them only in controlled labs.

Simple encoded payload:

Double-encoded:

Broken-keyword (split):

SVG-based:

Reminder: Always use labs like PortSwigger Academy, DVWA, or local test apps to practice.

8 - Operational advice for blue teams and SREs

- Integrate canonicalization + validation into application middleware.

- Alert on unusual encodings or nested encodings hitting sensitive endpoints.

- Maintain an allowlist of safe parameter patterns; reject unexpected types.

- Use runtime application self-tests: periodically inject safe sentinel strings (in staging) to validate sanitizers/CSP.

- Run fuzzing against your own apps (in staging) and include reflection detection as part of the test suite.

9 - Final thoughts (pentester’s perspective)

WAFs slow down attackers and cut noise, but the most successful XSS bypasses rely on mismatches: mismatches between the WAF’s decoding and the browser’s decoding, between lexical filters and HTML parsing semantics, and between client-side assumptions and server-side reality.

As a pentester: find flows where user data crosses contexts - URL → JS → DOM - and test those aggressively. As a defender: harden those crossings first.

Security is layered. WAFs are a layer. Proper encoding, CSP, and server-side validation are the foundation.

References & Further Reading

- OWASP XSS Prevention Cheat Sheet

- OWASP Content Security Policy Guide

- DOMPurify documentation (client-side sanitization)

- PortSwigger labs - XSS modules (for safe practice)